By: Anastasia Martynova,

student of the 11th term of the municipal educational institution / Secondary

School of General Eductaion, Aleksandrovka.

Teacher: Irina Vladimirovna Martynova

Teacher of the Russian language and literature with the municipal educational

institution / Secondary School of General Eductaion, Aleksandrovka.

The one who is jealously keeping the past in secrecy,

Will hardly be able to live in harmony with the future…

A.T. Tvardovskiy

Maria Friedrichovna Martynova

Mother said to my brother and me: if you want to learn about the history of your country, then set about studying the biographies of your grandparents. In fact, the history of my family is not a very common one: in 1938 my great-grandfather was repressed and shot dead; the other great-grandfather managed to hide from dekulakization somewhere in the Far East for a long time; he reclaimed land, ploughed and was finally rewarded for his diligent labour: he was designated to participate in the Exhibition of National Economic Achievement; and my grandmother, who I am going to tell about, became a special resettler.

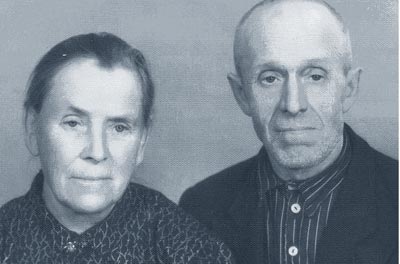

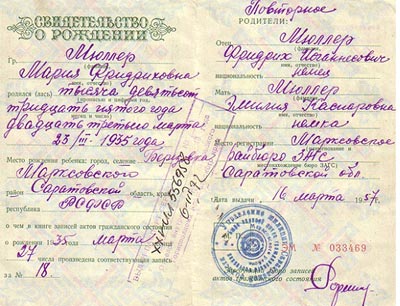

My grandma, Maria Friedrichovna Martynova, was born to a Volga-German family in Beresovka (Bekerdorf? Bäckerdorf?), Marxovsk District, Saratov Region on the 23 March 1935: Emilia (Emilie) Kasparovna Müller (1901-1986) and Friedrich Johannesovich (1902-1987).

Emilia Kasparovna and Friedrich Johannesovich Müller

Maria Friedrichovna Martynova’s birth certificate (second)

Besides grandma there were several brothers: Ivan (1929-1937), Fedor (1932-2005), Alexander (1937-1978), Ivan (1940-1989).According to my grandmother’s memories the family lived there at ease.

Friedrich Johannesovich performed different activity: he worked as a storekeeper, cashier and salesperson, and he disposed of a four term school education, which was not that bad for village people at that time. Emilia Kasparovna (three-term education) was part of a tillage brigade, who worked on a melon plantation, where they were growing water and honey melons, tomatos and cucumbers. On their little farm the family was breeding cows, goats, chickens and ducks; they were prospering. In the automn, in return for the daily work units they had managed to work off, the parents received vegetables, melons, which they used to salt for the winter (grandma still recalls their nice taste) and wheat, from which they used to bake an extraordinarily white and flavoursome bread. Later, in Siberia, the people were surprised, what a delicate rusk they were able to made from this very uncommon bread, which the Siberians had never seen before!

When the Great Patriotic War broke out, all this material prosperity abruptly ceased and a whole series of dramatic incidents began to take its coursde.

On the 28 August 1941 the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR passed the ukase “About the resettlement of all Germans living in the Volga rayons”. In accordance with this ukase “the entire German population of the Volga regions is to be resettled to other regions…::”.

The Müller family was forced to leave their home village together with their children and grandmother (already advanced in years; she was 76 at that time). The were the very last who left the place, for the father was working as a warehouseman at that time and he was reaching out food rations to soldiers till the very last moment. They had to leave everything behind: their solid house, fruit orchard and vegetable garden including a large crop; for a long time yet they could hear the mooing of the cows, the cackling of the barn fowls, although they had spread a great deal of grain feed right into the middle of the farmyead for them before finally leaving. They had fed all other animals for the last time, too. One of the little goats was running after the vehicle for a long time. They were forced to abandon their home. Grandma recalls that her grandmother hastily buried several icons and a book with religious contents.

They took along just a few personal things and foodstuffs. However, Emilia Kasparovna managed to take along her sewing machine, which later helped her to earn the money for their daily bread. Late in the 1990s grandma and her brother, theonly two survivers of the family, received a compensation on sixthousand (!) rubels for confiscated property.

Grandma told us that they were en route for a long time; at first, by steamer on the river Volga, then they were put on heated freightcars. She remembers that it was uncannily stuffy inside the waggon because of all the people, and that they were guarded. When the train stopped they were distributed porridge and soup. Almost until the 1990s grandma believed devoutly that the Sovietpower rescued her from fascism by resettling her family to such a remote place like Siberia. This belief became even more firm, after she learned that her village was completely burned down during the war, during fascist occupation. After the war her brother had insisted to visit the place and see their home village oce again; he reported that it was not existing anymore.

In connection with the Müller family another fatal error was committed: due to someone’s ignorance or insufficient orthographic abilities the surname Müller was changed into Miller, and their father’s nale Friedrichovich into Fedorovich. Thus, in order to claim the right of a state grant (in addition to the annuity payment) each member of a family of special resettlers is entitled to, grandma had to appear in court to prove that Maria Friedrichovna and Maria Fedorovna (this is how she was registered before the resettlement) arevidentic persons.

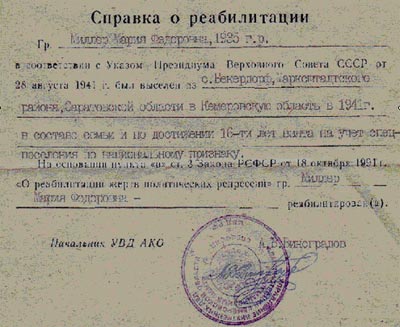

![]()

Fragment from the rehabilitation certificate

showing that surname and father’s name have already been amended

Upon their arrival in Siberia the family was allocated to the village of Chernyshovo, Kemerovo Region, where they were placed with the Chernyshevs. Grandma thankfully recalls them, because they themselves were hardly able to make a living, were impoverished, but always willing to help the resettlers and share the very last crumbs with them. But when it rains, it pours: in October they buried the grandmother. It is hard to say what she definitely died from: grief and sorrow, longing for her home or due to permanent underfeeding. Before leaving for work in the morning, Emilia Kasparovna would portion her 200 g bread ration for hear children and her old grandmother. She put the tiny portions into a small box (there was no table in the house); she threatened the children with serious punishment in case they would dare to even touch their grandmother’s share. But she, the grandmother, refused to eat her tiny piece of bread, sharing it among the children, as well. And the mother went to work hungrily. Thefather had already been called up into the trudarmy at that time.

When it rains, it pours: in November the arrested Emilia Kasparovna accusing her of a reputed lack of daily work units. Until today my grandmother recalls with tears in her eyes the day, when they came to fetch her mother tohether with some other women, the youngest child being just two years old. They were all crying bitterly, but nonetheless her mother was not allowed to go and say good-bye to them. Oma is still amazed about what her mother had to go through, how many things she was forced to learn the hard way, when she had to leave her little ones behind – all alone, left to their devices, in a ramshackled hut without windows, without food, without heating material and without any watch and care.

What must have been going on in her mind, during the long nights, when she rested on a cold plank bed praying for the rescue of her children! As if by a miracle the children survived! Fedia plaited little baskets, which he then took to the neighbouring village to exchange them against foodstuffs. Having returned home, he shared them with the little ones. Several times he returned, almost frozen to death, there was hardly any life inside him – he almost perished.

He held potatoes, some carrot or apiece of bread carefulls pressed to his breast. What a spark of hope could they leeach on? They were wering puttees or foot rags wrapped around their legs, all the other clothes were ragged, mended many times with great effort, or the used up the clothes of the adults, which, however, would glide from the shoulders at every movement. There was no hope, for almost all garments had to be exchanged against food. But you will always find some good soul in the world: Varvara Ivanovna Medvedeva, a warehouse keeper who lived right in the neighbourhood, commiserated with the children; on her way to work she would every now and then push something edible through the glassless window aperture – a pancake, a couple of potatoes. Life became slightly more easygoing in the spring and summer, when the herbs began to grow, the people could go berrying and look for mushrooms.

Wartimein hunger and cold are a traumatic experience, but for special resettlers and their families such circumstances turn out to be even harder. In the true sense of the word they ate everything which, in their opinio, was fit to eat. Until today grandma is not able to eat cucumbers: at that time she had once gobbled a frozen kolkhoz cucumber (early frost had spoiled the entire crop, and the cucumbers had become useless, as well). As for herbs, she could not eat orach – it made her sick.

In April Emilia Kasparovna returned home. She brought along a true loaf of bread, which was much more valuable than the most expensive confectinary. Her case had been revised and the people in charge had decided that she was to be released – giving her the advice to write a letter of complaint to those who had tolerated such a serious mistake. Emilia Kasparovna, however, had a different view on this: she herself had already been afflicted with the situation in a sufficient way,; she did not want anybody else to get punished. The biggest award and compensation for all torments was the fact that all her children had stayed alive, although it was hard to bear for her that her youngest son did not recognize her. He was tied to his grandmother’s apron strings (she was 70 years old then and had substituted his mother).

They ordered wheat, seed potatoes, flour and wool from the kolkhoz farm. Emilia Kasparovna and Fedor, her eldest son, built a dug-out, quite solid and warm, with treads. There even was a little corridor and one tiny window. They enjoyed weeding in the fields for they knew they would always find some old potatoes, which they could eat uncooked (Granny recalls their glassy, sweet teaste). And, of course, their food situation now became a little less grave: they managed to dig up a few frozen potatoes from the preceding year, and collected grain spikes from under the snow. But when the brigade leader caught any of them read-handed, he used to scatter everything on the ground again and made the horses trample it down. Of course, they ate everything unsalted, but Emilia Kaparovna suffered from this situation. Later, when she began to work as a stablehand, she managed to procure some of the salt, which she regularly administered to the horses; she washed and carefully dried it it and then used it tosalt her own meals. Early in the morning Emilia Kaparovna awakened her eldest son,who was to start the fire. He had to strike some metallic disk on a stone for a l ong time, until, finally, the sparks made a particularly prepared, washes and dried piece of cotton glow. She fitted the stove herself, and she did not only build one for her own family, but also for the neighbours. As heating material they were using little pieces of wood and brushwood, which the children gatherd in the forest and along the embankment during the summer. In case they ran short of the collected heating material before the end of the winter, they were forced to use up the fence surrounding their vegetable garden. Grandma still shows this extremely economic attiruted tody: she is still able to make use of the oldest rag, the tiniest piece of paper or any other material or object. Orchard and vegetable garden were worked by hand. Emilia Kasparovna broke up the entire garden area into little lots, asking each of her children to take the responsibility for one of them. And this is what they did: no weeds were to be found on their little vegetable batches. Grandma still enjoys gardenwork today.

The return of the mother did not only alleviate their food situation, it also brought an improvement with regard to their garments: she took grandmothers old skirts and started sewing dresses (one skirt made two dresses), as well as shirts and trousers made of sack cloth.

She was also sewing for the neighbours; she had taken along her sewing machine for the children’s sake! During the war, there was a children’s home which had earlier been evacuated from Leningrad; livestock farm (cattle and sheep) were attached to this home. Grandmother and mother yarned for the children living there; in return they received foodstuffs or worn out clothes. Grandma recalls that she had terrrible pain in her back, which was caused by this tedious, monotonous work; she was hardly able to sit, and her tiny fingers got all thin.

But childhood is childhood. Although it would only rarely happen, grandma succeeded from time to time to break away from her tasks and play with her ball (pressed from cowhair). But in the majority of cases she had to help with the house-keeping. For a while Emilia Kasparovna was working in a brigade responsible for the cultivation of tobacco, and my grandmother assisted her like an adult: she looked after the tobacco plants, helped with the weeding, watered the plants, cut off the petioles and sorted the leaves. It was a very hard job, particularly in hot weather, when a strange narcotic smell came from the little shoots causing headache and dizziness, until the people finally got sick. Due to these harmful effects, as a danger bonus, all workers received an extra sack of sugar – the one and only wealth at those times! Grandmother also helped with the drying of the tobacco plants: the very robust, thikck plants hat to be chopped up and then all individual pieves were hung up inside a specially constructed barn, about ten meters in height, for drying; this kind of a work was to be done exclusivels by lightweight minors with subtle fingers. Grandma did this work, as well. Once, some decayed wooden beam on which my granny was sitting, ruptured rightin the middle. Both, my grandma and the beam fell down on Emilia Kasparovna, who, after this incident, was suffering from a dropped stomach; apart from this she later became a crookback.

It was also very hard to water tobacco plants growing on top of a hill, although the river where they took the water from, bypassed the foot of the hill. It was grandma’s job to carry the water up the hill in two big buckets by means of a yoke.

For some time grandmother helped her mother to herd the kolkhoz cows. Grandmother looked after the cows; she was responsible for seeing that they did not run across the adjacent cemetery. In the meantime, Emilia Kasparovna was busily knitting skirts and shawls, which they later exchanged against foodstuffs. There were special resettlers from Latvia, as well. The Latvian women worked as milkmaids. They took pity on the almost starving girl and, taking a great risk, put some milk on the side and invited her to drink. They also filled milk into a big bottle, which grandmother took home for her brothers unnoticed. They cattle was driven out of the stables early in the morning, yet before sunrise. The ice-cold dew caused a burning pain on her bare feet; grandma used to warm them by putting them against the warm churns. Once, when driving the cows to the pasture ground and just crossoing the end of the cemetery, she stumbled and fell into an old grave. She was scared to death; she only just succeeded to call for hermother’s help by shouting continuously.

In 1944, when grandmother was nine years old, she one day went to school of her own accord, without asking her mother’s permission. She was sitting there the whole day – in a true classroom, in a true form. But this was to remain the one and only day in her life which she spent in a classroom! Having returned home she got punished for her freelancing: she was ordred to stay with her bothers and help with the household. Thus, my grandmother never attended any school. She learned everything the hard way by passing through the school of life. Later however, when her brothers came to school, she insisted to learn how to read an spell together with them. She used to train her spelling abilities by means of a little stick writing the letters into the snow or sand right on the embankment of the Chulym river. Grandmother has not completely forgottenabout hermother tongue: her parents tried their best not to speak German with their children. They wanted their children to learn Russian quickly, thus avoiding that they would distance themselves from the Russians. Fedor, the eldest, however, was able to read and spell German correctly. Still living in the Volga Region, he has managed to finish one term at the local school; later, he even got married to a German.

The father returned from the trud (labor) army in 1947 ( such a luck was not with many people at that time) and daily life became slightly easier, although he came back in poor health: due to hard labor in a limestone quarry he suffered from a disease of the lungs. During his time of being a construction worker he inadvertently cut off two fingers of his left hand and, on another occasion fell to the ground from great height. He had to stay in hospital for a long time. He was reluctant to recall the time of his being with the trud army, where he went through hell. Nonentheless, the head of the family returned home; there was now amother person to assist in daily housework and, what was most important, protect the family. Soonafter, they were able to afford a little calf, and the whole family looked after it: they feeded it carefully, got to know all the herbes it liked to be fed on; they did not have enough to eat for themselves, but the little calf always looked well-fed. However, there were some tragic consequences, as well: the calf would not allow any unknown person to come close, but just accept the members of the family it had become so familiar with; in case an unknown person came nearer, it began to use its horns and kick out. Hence, they decided to exchange it with a half-rotten, partly burnt down little hut without roof. Half-destroyed, almost a ruin, but a house, after all. A real house, not just a dug-out. Thus, life got under way by degrees.

At the age of 17 grandma began to work on the farm as a milkmaid. For a period

of nine years she was milking all the cows by hand. Apart from this, milkmaids

at that time had to muck out the cow barns themselves; they were to produce the

forage and feed the cattle. They were working all the time, without having a

single day off, having to be at standyba evenduring the night. Those were hard

times, the more since grandma, being young and unexperienced, were foisted on

the biggest cows, which were particularly hard to handle. Every now and then she

was helped by the wife of her eldesr brother, but nevertheless the whole

situation saddened her heart and gave her a hard time.

At the age of 17 grandma began to work on the farm as a milkmaid. For a period

of nine years she was milking all the cows by hand. Apart from this, milkmaids

at that time had to muck out the cow barns themselves; they were to produce the

forage and feed the cattle. They were working all the time, without having a

single day off, having to be at standyba evenduring the night. Those were hard

times, the more since grandma, being young and unexperienced, were foisted on

the biggest cows, which were particularly hard to handle. Every now and then she

was helped by the wife of her eldesr brother, but nevertheless the whole

situation saddened her heart and gave her a hard time.

In the winter they had to cope with undescribable difficulties: there was no electricity, the cow barns were not mechanized, they had to be mucked out by hand – admittedly, this was only done during the summer, when the frozen cow manure would gradually thaw; all summer the milkmaids were busily removing layer by layer, until the barns were finally clean.

In the winter, as well, when the huge cattle herd had to be watered, they drove them all down to the river, where they built some kind of a stretched well right into the ice. Then they chopped a hole into its middle; through this hole the “well” would fill with water from the bottom and the cows were able to drink. Once, the unfortified layer of ice caved in under the weight of the herd and the cattle almost perished by drowning. Nobody can imagine how the milkmaids had to drudge in order to rescue the animals! And grandmother herself almost drowned, as well.

Finally, she and her friend decided to get married, “even if their future husbands were just boneheads; someone from the neihbouring village best – for this was just far eniough away from the cow barns”. The first thing grandma bought herself from her first earnings were rubber boots (her first genuine footgear at all). However, she tried her best to conserve them: she went through the mud barfotted, and when the ground was all dry, she usually put on her boots. Regardless of labor on the farm, grandma enjoyed to make dates for the evening. She like to dance till day-break and then went back to work without having taken a rest.

Another popular pastime in post-war villages was the movie theater. Needless to

say that the people had no money for such movie screenings. However, there was a

possibility to work it out by berrying two glasses of currants or yielding a

defined number of cowhides to the shop.

You could also try to look through the little window hoping that it would remain

unnoticed by anybody; but this way of “free movie watching” was not accepted by

the adults, and children who were caught red-handed, were chased away at once.

Although it is hard to imaging, but although grandma and her friends had to cope

with such an immense amount of labor, they still found enough time to busy

themselves with knitting, a task which involved wearisome persistence in a

sitting position. And what extraordinary thinhs they made by adroitly using

crochet hook and knitting needles! Finest, daedal table-cloths, doilies, cussion

borders, covers and laces for underwear. They were in lack of yarn, had to

purchase every sindle thread, but there was no money. But then grandma began to

sell her handicraft and, now having a certain amount at her disposal, went to

the shop to buy new yarn. They were usually knitting at night-time, in the flare

of kerosine lamp, while being on stand-by on the farm, in a every single free

minute. Granny managed to keep some of these objects until today. A couple of

tablecloths and doilies are now exposed in a permanent exhibition shown by the

school museum.

In 1960 she got married to Fedor Nikiforovich Martynov and removed with him “far

waway from the cows”, not just to another village, but the the Krasnoarsk

Territory, which is adjacent to the Kemerovo Region – more precisely to the

village of Aleksandrovka. In 1961 and 1967 their two sons were bon. Here in

Aleksandrovka she first worked on a pig farm, and later changed to the calf

barn, where she stayed to work, until she finally reached the retirement age.

My grandma was decorated several times for her devoted work: she was awarded

medals “Of Labour Heroism”, banners of the “Winner of Socialist Competition”;

three times she was invested as “Shock-worker of Communist Labor”; many times

she received diploma and she is a “Veteran of Labor of the Krasnoyarsk

Territory”.

Maria Friedrichovna’s diploma

“Veteran of Labor of the Krasnoarsk Territory”

Even today, in spite of her aching legs (after-effects of running about barfooted through all her childhood and her longlasting work on the farm, when she spent day and night in rubber boots), she is unable to sit around passively. My sister and I were little children yet, when Mum was forced to go to work (there were not enough teachers in our village school), and grandma by no means wanted to send us to the kindergarten. Grandma did not only insist to look after us herself, she also taught us how to read and write and enjoyed reading out fairy tales to us. She still likes to read; in every free minute you can see her with a book or magazine in her hands. Until today she is bewailing the fact that she had no opportunity to attend school in her childhood and that she has no command of her mother-tongue. When she listened to how we pronounce German when getting prepared for our lessons, she was somewhat amazed how strange German words sound to her, how difficult their pronunciation is!

Finally, on the 18 October 1991, the government passed the Law “about the rehabilitation of victims of political repressions”. Many persons concerned did not live to see this law, for many of them it came too late.

Many special resettlers of the year 1941 later left the Kemerovo Region, they even left Russia in order to spend their evening of life in Germany. Among those who decided to emigrate was the family of grandmother’s brother. They left the country in 2003 and there, beyond the border, the new generationof the Millers was born. Grandma herself is unable to imagine, which motives might bring someone to the decision to leave this place, to leave the graves of one’s parents, brothers and sisters. For this is the place where she found her new home. She say: “The home of my children and grand-children is my own home, as well…”

Taking stock of my research work I would like to note that my granmother’s

biography is quite unusual! She gives an exemplar of courage, vital pertinacity

and belief in the good. In spite of the fact that grandma suffered a lot, she

always remained a good soul, full of love for

others.

Annotation: unfortunately, we were unable to find any photos taken in grandmother’s childhood. Most likely, those pictures takenbefore the war got lost during the war or were destroyed, when the children were left behind without care. The only thing those little kids had in mind were how to fight hunger and cold.