“Man in history. Russia – 20th century”

Author: Yevgenia Pankova

Form 11 b, municipal educational institution, Secondary School No. 115 of

general education, city of Krasnoyarsk

Project leader: Olga Leonidovna Vosnyuk

Teacher of history and social studies

Municipal educational institution, Secondary School No. 115 of general education,

city of Krasnoyarsk

The present paper is dealing with a variety of problems the Volga Germans had to face during the resettling process in the first years of the war and with the fate they were to meet in Siberia.

Tremendous difficulties during the removal and when trying to organize their life and get settled in the new places of residence, acclimatisation and psychological strain, problems with the language, as well as humiliations and abasement from the part of the local residents towards these representatives of a different nationality are basic parameters addressed by the author. She tries to detect and trace them by describing the hard lot of her own grandmother – Frieda Ivanovna Kerber (Körber?), for which reason her paper is turning out to be utterly emotinal.

It is based on interviews held with the author’s relatives (mother and grandmother), but also shows the rich photo archive of the family.

The author reveals the fate of a concrete Soviet individual, stressing out the importance of the strength of mind and the est of life for the development of personality. An interesting phenomenon in this connection is the exemplification of many resettlers’ longevity.

The author did not merely work on this paper to study and research the mere historic contents of that time, but to reveal the ethical and moral backgrounds, which are important for the role and meaning of each concrete personality within the global process of history. This is to be the ethical and moral balance of the present paper.

Project leader: O.L. Bosnyuk

1. Repressions against the Russian Germans – one of the goriest crimes of

stalinism.

2. The long, troublesome way to Siberia.

3. The first years in Siberia: hunger, cold and humiliations.

4. The arrest of the mother.

5. Aunt Sofia: rescuer and victim.

6. Zest for life – the basis for longevity.

7. Reflection on the life of a simple Soviet woman – a piece of history.

Dedicated to my beloved grandma

Frieda Ivanovna Kerber …

The repressions against Russian-Germans are to be considered as one of the most atrocious among the numerous crimes committed under Stalin’s rule in connection with World War II. The deportation of Germans from fascist Germany after the outbreak of the war was the beginning of the policy which focussed on the liquidation of the entire people of Russian-Germans. In July 1941 the Crimea Germans were displaced from their places of residence, in August 1941 the Volga germans, in October 1941 all Caucaseans of German origin, and in 1942 all Germans from the Leningrad Region were resettled. More than 800 000 people were sent away to Middle Asia, Kazakhstan and Siberia.

During the reign of Catherine II Germans resettled to Russia in droves. The empress was in urgent need of manpower to reclaim land in new territories and to defend the frontieres. The resettlers mainly relocated along the river Volga. By a special manifesto they were granted a number of benefits and privileges. However, after the death of the sovereign, the attitude towards Germans changed considerably; benefits and privileges were abolished step by step. The next wave of repression they were forced to tolerated happened in the 1930, under the rule of the Soviets. But all this was just the foreplay of the most extensive, fatal and protracted measures of repression, which started with the passing of the ukase of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR “About the resettlement of all germans living in the Volga Rayons”.

My grandmother, Frieda Ivanovna Kerber (maiden name Airich) belonged to those

Germans who were affected by the resettlement action from the Volga in 1941. At

that time she was 11 years old. She lived with her family (father and four half

sisters on the mother’s side) in the village of Rainwald situated at the river

Volga not far from Saratov. Unfortunately, my grandmother does not recall, how

they were informed and who passed them the news about the resettlement of all

villagers, but she does remember that they were given twenty-four hours to pack

their belongings. The people did not have the faintest idea about how long they

would be on the way; for that reason they took along just very few things,

mainly foodstuffs (which could be preserved for some time) and everything else

they might need. The villages were forced to leave their houses and farms behind;

they had to leave their home areas without knowing where they would be taken to

and for which reason.

My grandmother, Frieda Ivanovna Kerber (maiden name Airich) belonged to those

Germans who were affected by the resettlement action from the Volga in 1941. At

that time she was 11 years old. She lived with her family (father and four half

sisters on the mother’s side) in the village of Rainwald situated at the river

Volga not far from Saratov. Unfortunately, my grandmother does not recall, how

they were informed and who passed them the news about the resettlement of all

villagers, but she does remember that they were given twenty-four hours to pack

their belongings. The people did not have the faintest idea about how long they

would be on the way; for that reason they took along just very few things,

mainly foodstuffs (which could be preserved for some time) and everything else

they might need. The villages were forced to leave their houses and farms behind;

they had to leave their home areas without knowing where they would be taken to

and for which reason.

When the time to leave had come, they were aksed to board waggons, which actually were not intended for the transportation of human beings, for there were no windows at all, there was nowhere to sit down and it was terribly hot – hence many fell ill, particularly children. There were even events of death. Days were passing by, but still the people were kept in the dark about what would happen to them next. They did not even have the opportunity to ask, where they were going to and which places the train was passing by, for they were unable to speak Russian. There were just some isolated people who could say a few sentences in Russian (one of them was a good friend of my grandmother’s father), but nobody would give them any concrete answer.

The people began to panick, envisioning all kinds of variants of their fate.

many were of the opinion that they were taken to remote places in order to shoot

them or destroy them by any other means. However, the trains went on and on. Of

course, they stopped at a station every now and then, for provisions had run

short since long; fresh food had to be bought. Under such conditions the people

were on their way to nowhere for about two weeks. The trip took that long,

because they did not take the direct route to Siberia, but made a long way round

all through Kazakhstan. There my grandmother, her mother and sisters had nearly

been left behind without patriarch. Grandmother’s father Ivan had left the train

during a stopover to buy some foodstuffs. On his way back he nearly missed the

train; in the very last second he managed to catch the last waggon of the train;

at the next stop he returned to the waggon where his family had been anxiously

waiting for him.

The people began to panick, envisioning all kinds of variants of their fate.

many were of the opinion that they were taken to remote places in order to shoot

them or destroy them by any other means. However, the trains went on and on. Of

course, they stopped at a station every now and then, for provisions had run

short since long; fresh food had to be bought. Under such conditions the people

were on their way to nowhere for about two weeks. The trip took that long,

because they did not take the direct route to Siberia, but made a long way round

all through Kazakhstan. There my grandmother, her mother and sisters had nearly

been left behind without patriarch. Grandmother’s father Ivan had left the train

during a stopover to buy some foodstuffs. On his way back he nearly missed the

train; in the very last second he managed to catch the last waggon of the train;

at the next stop he returned to the waggon where his family had been anxiously

waiting for him.

After two weeks they reached their final destination – in the Novosibirsk Region,

Burabinsk District, in the village of Syusya. Upon their arrival almost all male

individuals were called up to the trudarmy; Ivan, my grandmother’s father, was

among them, as well as the father of her future husband – Ivan Karl. Grandma’s

family was allocated one room in a house, where another two families had already

found accomodation, as well. Inside the house it was terribly cold, and there

was nothing to heat the stove with. For that reason they decided to use reed,

which they picked from the nearby lake. After a certain time the family removed

to a dug-out; fortunately, it was not that cold inside.

After two weeks they reached their final destination – in the Novosibirsk Region,

Burabinsk District, in the village of Syusya. Upon their arrival almost all male

individuals were called up to the trudarmy; Ivan, my grandmother’s father, was

among them, as well as the father of her future husband – Ivan Karl. Grandma’s

family was allocated one room in a house, where another two families had already

found accomodation, as well. Inside the house it was terribly cold, and there

was nothing to heat the stove with. For that reason they decided to use reed,

which they picked from the nearby lake. After a certain time the family removed

to a dug-out; fortunately, it was not that cold inside.

The lack of warmth, however, was not the only problem they had to cope with: they were used to mainly nourishing on the fruits and vegetables which were growing in their own garden, but when they arrived in their new place of residence, it was autumn. Hence, the people had nothing to eat. Many died from cold and hunger, and my grandma almost perished, too. At the time when she began to feel really bad, her mother was at work, harrowing the field by means of oxen (later my grandmother helped with this). Her paternal aunt carried her outside and called the neighbour for help. The neighbour, an old woman, brought along some milk and immediately began to spoon-feed the girl, who would apparently died very soon. Fortunately, it survived. The aged neighbour felt sympathy with the girl’s family; hence, the idea of asking Frieda to herd her cow, crossed her mind; and after my grandmother had driven the cow back home in the evening, the neighbour offered her a glass of milk.

Thus, they spent winter and spring in hunger and cold. Early in the summer they were supposed to plant potatoes, in order to have a chance to survive the next winter. But where should they take potatoes from, even if they only needed a small quantity of them? Being hard up, grandma’s family began to pick potatoe peels which the local residents had littered and tried to grow them – at least hoping that this would result in something edible. However, it did not work witout the aid of some good people, either. One woman observed how they were struggling; she gave them a pailful of potatoes, although they were quite a few and small ones only, but nonetheless this was a very important, good deed.

Unfortunately, not all local residents behaved good-naturedly towards the German

newcomers. The vast majority of the population was very aggressive. The Russians

(children as well as adults) came up with offending lines, they cursed the

Germans and even punched them. Some were struving to cheat the Germans. Just to

give an example: among the things, which granmother’s family had taken along,

there were some clothings – all in good repair, practically new. And now, weak

from hunger, standing at the abyss of life, they were forced to exchange the

clothes against something to eat. Grandma recalls one specific moment. Among all

these garments there was a beautiful white cardigan, which granmother’s family

exchanged against a certain quantity of frozen sauerkraut.; and when they later

unfreezed it, it turned out that the box containing the sauerkraut was half

filled with ice.

Unfortunately, not all local residents behaved good-naturedly towards the German

newcomers. The vast majority of the population was very aggressive. The Russians

(children as well as adults) came up with offending lines, they cursed the

Germans and even punched them. Some were struving to cheat the Germans. Just to

give an example: among the things, which granmother’s family had taken along,

there were some clothings – all in good repair, practically new. And now, weak

from hunger, standing at the abyss of life, they were forced to exchange the

clothes against something to eat. Grandma recalls one specific moment. Among all

these garments there was a beautiful white cardigan, which granmother’s family

exchanged against a certain quantity of frozen sauerkraut.; and when they later

unfreezed it, it turned out that the box containing the sauerkraut was half

filled with ice.

All this cheating, these mortifications and humiliations on the part of the Russians were legal when taking into consideration that the Soviet power was at least not really keen to give any explanations on the occasion of the resettlement of the Germans; however, they did not forget to represent the Germans as spies and saboteurs.

However, hunger and insults were not yet all what made up the unhappiness of the

Airich family. In 1943 the head of the family, the mother, was arrested and

sentenced to six years – just because she and some other women had met in the

evenings to read out texts from the Bible in their mother tongue. Thus, she had

to leave her five children behind, who, from now on, were to somehow get along

themselves – among people who were all prejudiced against them. All children,

apart from the two elder ones (my grandma and her older sister Emma) were taken

to a childrens’ home.

However, hunger and insults were not yet all what made up the unhappiness of the

Airich family. In 1943 the head of the family, the mother, was arrested and

sentenced to six years – just because she and some other women had met in the

evenings to read out texts from the Bible in their mother tongue. Thus, she had

to leave her five children behind, who, from now on, were to somehow get along

themselves – among people who were all prejudiced against them. All children,

apart from the two elder ones (my grandma and her older sister Emma) were taken

to a childrens’ home.

When Aunt Sofia, mum’s sister, learned about the fact that the childrenwere now supposed to grow up without their mother’s care, she immediately decided to fill in, although her own fate was not painted in iridescent colours, either. Her family had been dispossessed in 1930 for being from among the so-called kulaks; they were sent to the town of Achinsk situated in the Krasnoyarsk Territory, where all her family members died (two children and her husband). As surviving member of the family she decided to return to her home village. She went on foot from Achinsk to Saratov and then proceeded for the village of Rainwald. She lived there for about one year, until she was arrested for having returned home – and maybe for some other reason yet. They took her to the town of Kirov, where she had to work for the trudarmy. Many, many years later she received the permission to leave the place and live with her nephew. She stayed in his family, until Julia, the mother of the children, returned home; nevertheless, she did not abandon them after this moment, for they were her closest relatives who were still alive.

Before the resettlement things in my grandmother’s childhood flew smoothly; her

infanthood was not cheerless and unkind at all. Life in the German village was

full of joy and lightheartedness (at least for the little girl). She was

surrounded by her close relatives and friends, but the main thing was that they

were all in good health and - alive. The little girl was not aware of what

permanent cold and hunger meant to human life; she was not even able to imagine

what kind of obstacles life had in store for them, and she would have never

believed how unkind and even brutal human beings could be. However, in 1941, she

was to learn all these horrors the hard way; she had to experience the meaning

of entire weakness and exhaustion, of approaching death from starvation, and she

very well realized about how you feel having to live without mother for six

years and without father – for the rest of one’s life!

Before the resettlement things in my grandmother’s childhood flew smoothly; her

infanthood was not cheerless and unkind at all. Life in the German village was

full of joy and lightheartedness (at least for the little girl). She was

surrounded by her close relatives and friends, but the main thing was that they

were all in good health and - alive. The little girl was not aware of what

permanent cold and hunger meant to human life; she was not even able to imagine

what kind of obstacles life had in store for them, and she would have never

believed how unkind and even brutal human beings could be. However, in 1941, she

was to learn all these horrors the hard way; she had to experience the meaning

of entire weakness and exhaustion, of approaching death from starvation, and she

very well realized about how you feel having to live without mother for six

years and without father – for the rest of one’s life!

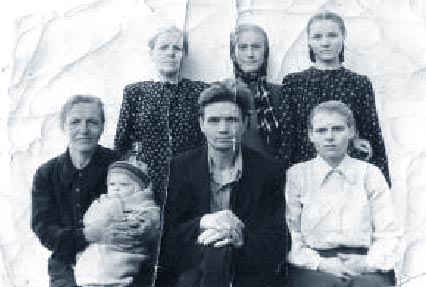

One of the most striking indications for the steadfastness and love of life of people during the Soviet epoch is the phenomenon of longevity of many of my grandmother’s close relatives –people who were to face repressions, who suffered from cold, hunger and mortifications, but nonetheless managed to keep their spirits up. Photos from grandma’s personal archive prove this statement. Joined by their fate the outcasts and outlaws stuck together, their family bonds were incredibly strong, and grandmother talks about each of her relatives in warm words. A family bond must never break between the generations.

The Airich family

My grandmother was to meet the same fate as millions of Soviet women of those times, and it was closely connected to the village of Syusya, where the repressed Germans were deported to.

Frieda Ivanovna as a construction worker

Frieda Ivanovna was working for some construction project for a long time, doing heavy physical labour, such as carrying heavy stocks – or shiftwork, which was no exceptional aspect of life at a time, when the jobs held down by women and men were hardly different from eachother; they were all on the same level, prepared to help with the “construction of communism and a bright future” in an utterly self-sacrificing way.

Frieda Ivanovna’s and Ivan Karlovich’s wedding

Later she worked for the kolkhoz farm as a milkmaid. She had to get up very

early in the morning and carry heavy pails for a miserable (more precisely –

fictive) wage. And she was completely disenfranchised. To add insult to injury,

grandmother was “bound to the clod” like all the other kolkhoz workers for a

long time. There was no possibility to go to any other place, for she did not

even have an identity card!

Later she worked for the kolkhoz farm as a milkmaid. She had to get up very

early in the morning and carry heavy pails for a miserable (more precisely –

fictive) wage. And she was completely disenfranchised. To add insult to injury,

grandmother was “bound to the clod” like all the other kolkhoz workers for a

long time. There was no possibility to go to any other place, for she did not

even have an identity card!

When grandmother’s health did not allow her to work out of doors and carry heavy loads, she accepted a job in the village kindergarten. It never occurred to this brave woman to twiddle her thumbs; she was not accustomed to sitting about and have a rest. Even now, in her nicely arranged flat (we took her in in 1996, after having noticed that she could not manage with her household anymore), she is pacing around all the time among her grownup grandchildren, and her permanent assistance with the housekeeping is noticeable for all of us, as well as we feel her boundless affection towards us!

I n spite of all strokes of fate, privations and humiliations this wise woman

maintained her zest for life, an astonishing fact even for us, the young people!

Meanwhile; Frieda Ivanovna accomplished the 76th year of her life, and many a

people would certainly envy her for her long memory. Grandma recalls every

single phase of her life, on which the Soviet power left a burdensome stamp. For

each stage of her path of life is enwrapped in Soviet ideology – that’s our

history, and grandma’s fate – a tiny part of it.

n spite of all strokes of fate, privations and humiliations this wise woman

maintained her zest for life, an astonishing fact even for us, the young people!

Meanwhile; Frieda Ivanovna accomplished the 76th year of her life, and many a

people would certainly envy her for her long memory. Grandma recalls every

single phase of her life, on which the Soviet power left a burdensome stamp. For

each stage of her path of life is enwrapped in Soviet ideology – that’s our

history, and grandma’s fate – a tiny part of it.

1. Interview with my grandmother F.I. Kerber (the hero of this research paper)

2. F.I. Kerber’s photo archive

3. Interview with M.I. Pankova (the author’s mother)