Stages of a long trip

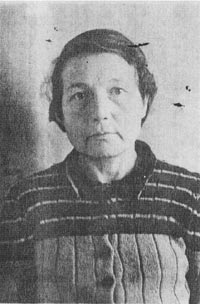

Ivonna Bovar was born in Switzerland in 1902. Could her mother, a housewife named Marmilon-Josefina, could ever have foreseen, what kind iof a tragic fate her own daughter was going to meet?

We do not know much about Ivonna’s childhood – just that she graduated from

college (9 terms) and then, at the age of 16, began to work for the Dupont

Lottery Office as a shorthand typist. At the same time she learned to play the

violin and gave up her previous job, in order to become a professional violonist.

We do not know much about Ivonna’s childhood – just that she graduated from

college (9 terms) and then, at the age of 16, began to work for the Dupont

Lottery Office as a shorthand typist. At the same time she learned to play the

violin and gave up her previous job, in order to become a professional violonist.

The little private orchester used to play in the „Cinema“, accompanying silent movies by music, which corresponded to the sentiment of the scenes, and everything had certainly turned out to be wonderful, unless there had not been signs of technical progress. As from 1927, besides orchestras, radiolas appeared in the cinemas, and when, finally, they began to show talking films only, background music produced by an orchestra was no longer needed. For a period of five years Ivonna resumed her previous work, but these were neither the longest, nor the most difficult years in her life – as it should turn out only later.

In 1932, with some retardation, and here you will certainly agree - an unfortunate event happened to her, which made her further life coma apart at the seams: Ivonna fell in love with a Communist. In actual fact, the Pole Mark Schalks was no party member at all, but he took very actively part in what was called the labour movement at that time: meetings, demonstrations with proclamations and all that stuff.

They had just been married for a short time, when the police in Geneva shooted down members of a mass demonstration (13 dead people and 60 injured – wherby I must admit that I never heard of any mass labour movement in Switzerland before). The government expelled Young Schalks, one of the organizers of the demonstration, from the country for being an undesirable alien. Ivonna – stayed behind! But she decides to follow her beloved husband. 20 years later she writes in her autobiography: „We started the life of nomadic people. We lived in France, Portugal and Spain, but my husband did not succeed to find a job. I had short-term jobs with a French export company, the French University in Madrid etc.“ But this is not going the hardest, most upsetting time in her life, either.

Obviously, the shooting in 1932 caused quite a stir within the Swiss society, and ine year later a socialist government came into power in the Geneva canton. Mark addressed himself to this new government asking fort he permission to return home; his appeal was accepted,but the federal government in Bern objected: it turned out that Schalks had been expelled from the country forever. Ivonna returned to her native country alone – but she follows her husband’s path of life up to the very end.

Apparently, Mark Schalks was quite a well-known man among people from certain circles, fort he famous French writer and Communist Jean-Richard Blok had an active part in his further fate. He vouched for Mark in front oft he USSR government, so that they granted him the soviet citizenship. Ivonna left for her parents in Switzerland, but not for a long time: „A wife belongs to her husband“, even when they cohabitate, - as we would like to add. In 1936, by the aid of the MOPR (International Red Aid; translator’s note), she follows Mark to Moscow.

This is – true love! And you cannot just compare it to Shakespearre’s passionate characters.

In Moscow Mark gave French lessons at the Institute of foreign language, while Ivonna Bovar worked as a typist for the French Radio Committee editorial office. Eshov’s - and later Beriya’s – people afflicted the country without wasting any opportunity to doing so. However, the alien couple lived happily for the time being. Then, in October 1940 Mark was arrested, and one month later they came for Ivonna, as well. At this point we are not going to attempt to imagine, what kind of a torment she had to go through during this month. She was realistic enough to comprehend, what had been going on in the USSR fort he past few years. She was very well aware oft he fact that acquaintances of her disappeared all of a sudden, she had read about show trials and obviously knew the meaning oft he abbreviation ChIR (family member of a traitor to his country; translator’s note). She was seriously affected by Mark’s situation and had, of course, been waiting for her own arrest; maybe, she even felt relieved, when they finally came for her.

An NKVD Special Board sentenced our violinist and typist to an eight years‘ camp detention by using a formulation which would never have been used in any civilized country of the world: „Suspected of espionage and anti-Soviet agitation“; she was sent to the North-Kuzbas camp, OLP N° 1, near Yaya railway station, which is situated not far from Kemerowo. Her invalidity saved her from being forced to do hard labour. There Ivonna acquired the skill to work as a bobbin lace maker, knitter and producer of finest embroidery. Throughout all those long eight years she was at pains to find out at least some small piece of truth about her husband’s fate. Finally she learned the following: he died in the Dalstroi in 1942 – although nobody could unerringly confirm that this was really true.

In November 1948 Ivonna Bovar‘s term of imprisonment came to an end. She intended to go back home, but the people living there had not forgotten about her, either. A registered letter from the Swiss ambassador arrived in the camp, in which he informed that Ivonna‘s mother was still residing in Geneva, on the Emien-Dupont street, and that she was very concerned about her daughter’s fate. On her request, die Swiss authorities had ordered the ambassador to find out details about Bovar’s whereabouts and then make sure that she could return home in case this was her own wish, too. Alas! Of course, this was what she wanted – return home to where her old mother lived, after having lost her husband and experienced lots of misery in the camp. Unfortunately, the letter arrived too late; it had been sent only in January 1949, when its intended addressee had already left the camp. Four months before, however, the ambassador had sent a telgram with a paid return receipt and a money transfer in the amount of 300,- rubels tot he same address, but the prisoner had neither received letter nor money. The telegram said that they suggested her to direct herself tot he authorities with the official request to issue a Swiss passport in her name. Bovar did not know anything about the efforts of her mother and the government.

She was „released“ shortly before the end of her camp term, taken to Krasnoyarsk and one month later sent in to exile. The hamlet of Podtyossovo in the Yeniseisk District, can still be numbered among the places of internal exile today, but how did the place look at that time - 50 years ago? Literally speaking, it was a one-horse town! Ivonna tried in vain to find out any information about how long she would have to stay in exile, but the documents which now lie in front of me, do not give any indication on the term at all. And, in actual fact, it not been fixed in writing! A few months after Ivonna’s arrival Ariadna Efron, the daughter of Marina Tsvetaeva, arrived from Krasnoyarsk, who had been exiled tot he Turukhansk District. She had even been told: the term of exile is indefinite. Ivonna, however, was forced to agonize over this appalling uncertainty.

„During my stay in the camp I had become acquainted with my second profession – artful embroidery. But even in Yeniseysk they did not need this kind of a profession, so that I received just reactions on my job applications … What shall I, a lonesome exile, do without any help and support!? I insistently ask you to please make the situation a little easier for me by allowing me to leave for another place, some more significant town than justYeniseysk, a place where I will have the possibility to earn my living in accordance with my strength and abilities“. You will probably not believe it, but Ivonna asked to sen her to Norilsk . ... Only after five months she succeeded to find a job – as a hospital medic, but nobody except God knows, what she lived on during all these months – most probably, she met good people, who were prepared to helping her, for both embankments oft he Yenisey to the North were typical exile regions, after all. Later, the Swiss violinist had to work as a home help in various households in the settlement of Podtyossovo.

We have to note that Ivonna managed to become fluent in the Russian language within about 13 years – a comparatively short period of time. Anyway, this is attested by her handwritten autobiography: a good literary style without any mistakes; well, camp life probably made a contribution to this. And the operational authorized representative, who was responsible for her in Yeniseysk, even wrote: „In compliance with the original“.

One must obviously have been born in a free country, in order to be able to fight for oneself like Bovar did – even though she had spent eight long years within the GULAG system as a prisoner. She writes to the Ministery of National Security in the Moscow Region claiming the return of her belongings, which were confiscated from her during the arrest. They reply: since it was impossible for us to take them into custody, we gave them away the the State funds. She sends another petition, requesting to leave the country, but upon further inquiry of the Krasnoyarsk MGB authorities they reply from Yeniseysk: we never received a petition of this kind. Instead, in 1952, Ivonna has to acknowledge by her signature that she was informed about the fact that: any attempt to escape from the place of internal exile will be punished by 20 years of forced labour.

And then dies Stalin. Criminals get amnestied, but also political prisoners Häftlinge have good reason to hope for the better. Already in April Ivonna writes a letter to the chairman of the USSR Supreme Soviet, Klimentiy Voroshilov: give me the permission to leave for my native country, and in June, having received a positive reply, she sends another letter to the Minister of Internal Affairs, Lavrentiyj Beriya: „I kindly ask you to comply with my request to release me from exile ... and give the necessary instructions to the competent MVD organs. I furthermore ask you to provide me with financial means for my trip to Moscow. As soon as I am there, I can count on the help of the Swiss ambassy“. But at that time Beriya had already been „exchanged“ against somebody else; such affairs were no loger his business. Finally, almost at the same time, the Swiss diplomatic mission learned Ivonaa’s address from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and sent her n application formfor the issue of a Swiss passport. Once again she writes to the Ministry of Internal Affairs: excuse me, but how can this be – even Voroshilov has already given me the permission to leave the country; hence, please finish this little formality and ... release me from exile! The Ministry of the Interior replied by return of mail: „There is no reason at all, while your exile status should be annihilated“.

Had all been said and done? No! Ivonna Bovar no gets the full support of her fellow countymen and bombs almost weekly all possible authorities and instances with letters and telegrams; she receives contradictory replies, but- she succeeds to completely confuse the officials. Finally, in September, she receives her Swiss passport, and in Oktober – oh, as if by a miracle! – the head of the Krasnoyarsk MVD authorities in Krasnoarsk gets the instruction from Moscow: „To be presented to Bovar ... Swiss national passport ... to be released from exile. Permitted to leave for her home country!“ Half a month later Ivonna Bovar was released, her criminal record liquidated. She returned to Geneva, were she died at the age of 82.

An unusual fate, but this is not the end of the story ye. In 1997 the chairman of the Krasnoyarsk „Memorial“ organisation, Vladimir Sirotinin, received a letter, by which he was informed that, due to the efforts of the Swiss journalist Daniel Künzli and theMoscovitan cinematographer Radiy Kushnerovich, Bovar – the one and only Swiss citizen, who got between the grind stones of the NKVD system, had been rehabilitated. Apart from this, the author of the letter asked for the possibility and permission to make a film about Ivonna’s life inYeniseysk. Of course, Sirotinin helped the man from Switzerland..

Anyway, we will find some ethic collision in this place, as well, which surprises. Why was Ivonna’s rehabilitation so important for the journalist – the more so as it was accorded posthumously? For her descendants sake? But, first of all, she died as an entirely lonesome person; secondly – anti-Soviet agitation rather refurbishes someone’s biography, instead of spoiling it. Last but not least the request for rehabilitation means, even though indirectly, the acknowledgement of of the legitimation of Stalin’s regime in general - and partly of its jurisdiction, as well. Well, for you, law-abiding Europeans. This is something you will highly appreciate, but Ivonna cannot care less – she has already left this world.

Anatolij Ferapontov

Materials from the Krasnoyarsk „Memorial“archives were used for this article.

„Komsomolskaya Pravda“, 21.08.98