Before the deportation to Siberia Iraida Ivanovna‘s (born 1938) family lived in Marxstadt. Mother Ella Johannovna (born 1914) was able to read and write, she spoke German and Russian. After an educational training in Moscow she worked as a telegrapher. The father – Johann Johannovich (born 1911) – worked as a carpenter and built doors of the highest category. The elder sister was named Olga (born 1936). The family had a good life: they had their own house with a big farmstead. The grandfather was a trader by profession and owned a shop. Iraida Ivanovna recalls the dolls being sold in the shop. It was situated on the other side of the road, just opposite their dwelling house.

In the autumn of 1941 they were deported as all the other Germans. Several families were “tipped out” in the village of Yelovka. There were posters with illustrations of Germans wearing helmets with devil’s horns, and many people thought that the Germans were horned creatures. The local residents came running up, in order to have a look at these German families. It turned out that they were people like themselves. The newcomers were distributed into different houses, stoves were heated and the deportees were fed. The mother was pregnant at that time, a son was born soon-after – Vova, who did when he was still an infant.

Uncle Karl (the father’s youngest brother) got his professional training at the flying school, and when the war broke out, he was already able to fly by himself, but he was deprived of the flying license.

When the father received the conscription order he was very worried, about having to leave behind his wife and the three children. Ella Ivanovna had no idea about cattle breeding and did not know the first thing about how to do all other required agricultural work. For this reason Johann Johannovich addresses himself to the party district committee in the hamlet of Karatuskoee to get the permission to re-settle his family. They were willing to make concessions by accommodating them in some basement dwelling.

At first the mother got a job with the consumer goods combine, where she had to comb wool and full felt boots. As she had to work in night shifts, she placed her children in a kindergarten, where they spent the nights as well. In this kindergarten there lived and worked „Baba Zhenia“; she had no children of her own. She helped Ella Johannovna as much as she could; she took the children to where she lived, took care of them, until their mother returned from work: „Lena, while you are at work, I will take care of the children“.

Ella Johannovna had lived in a town before the deportation; hence, she was not able to do all the agricultural work requested in the countryside. Once the landlady, where she lived with her daughters, sent her at frost into the forest to get firewood. The landlady did not think about the necessity to explain to her, what she was exactly supposed to do. Ella Johannovna took the sled and left for firewood, but she forgot to take along an axe. Hence, she collected stakes and switches. Later she believed to see little fires; she was of the opinion that somebody had lit a campfire. In actual fact, as turned out later, there were wolves, which had started to surround her. Only too well that a forest warden passed with his sledge and the wolves were chased off by its noise. The warden took her along to his little house. She tried to explain the situation to him, but he took her to a militiapost, for he had understood that she was a deported German woman. In the meantime, the landlady was all worried, because she had omitted to explain her, what to do, but afterwards apologized.

They had to move many (27) times. Either foreign people took them in or they found a sanctuary themselves. Once they lived with a woman who had a five year-old son. The mother did the laundry there, hung it up for drying – it was stolen. They had nothing to eat. In order to muddle through and survive, they gathered potato peels, berries and herbs. Under major difficulty they organized their own vegetable garden and grew corn for some time.

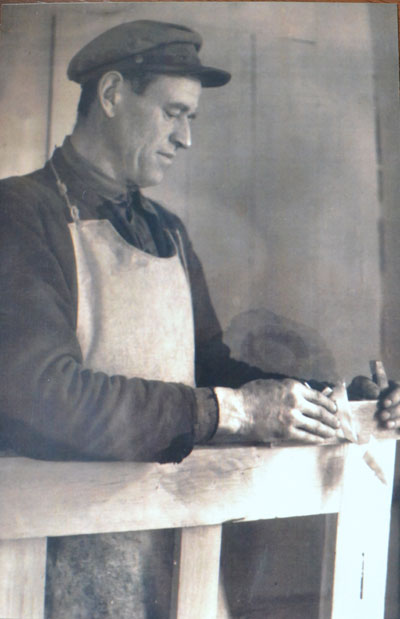

After the father had returned from the labor army (he did forced labor as a lumberjack) in 1945, the family was allocated a place to live. The father talked a little bit about the time he had spent in the labor army: he had a hard and dangerous job, which, amongst others, was due to the fact that there had been lots of criminals, who used to maltreat the other prisoners. The father caught a serious cold which affected his lungs and ended in permanent health implications. His bad state of health was the reason for why they had sent him home. He got a job for some forest enterprise and also worked as a stable-hand. Later he worked as a carpenter. In Alma-Ata he ornamented the congress palace with carvings. Inside the building there was a portrait of Johann Johannovich. He also had students, who learned this trade from him. They crafted furniture for clubs and other public institutions and organizations.

After the father’s return from the labor army another son – Vitya – was born.

The parents communicated in German, while they spoke Russian with the children. Wenn they were offended and ragged on at school, the daughters begged their parents not to speak German anymore, when guests were at home: „They mock us anyway, but if they hear you speak German, things will get even worse”. Much later the girls still understood a few words of German, but it had already become a foreign language to them.

When the girls were at school, Iraida Ivanovna always felt „as the scum of society“, for she was cursed at as a „fascist“. She recalls that, whenever she was asked something in German during the lessons, she stood up, but refused to say a word, although she knew the reply. She was very uncomfortable with the situation. She just did not want to give reason to anew invectives. Later, when people started to call them Russian Germans, she was able to breathe more deeply.

Iraida Ivanovna recalled one particular incident: she was walking with her friend along the little river, it was spring and there was high tide. On their way back home from school they had to cross a bridge. Suddenly, like a bolt out of the blue, the friend started screaming at her: „Fascist “ - and ran away. She ran and ran and – fell into the river. However, she managed to get back to the riverbank herself, without any help. At home Iraida Ivanovna reported what had happened. The girl’s mother (Aunt Lipa) arrived to learn what had happened. Obviously her daughter had told her that Iraida Ivanovna had jostled her and that she, as a consequence, had fallen into the river. Having learned what had actually happened, Aunt Lipa punished her daughter. The following day the two girls went to school again, as if nothing had happened at all. In spite of this incident the girls continued to associate with each other.

The grandmother’s brothers lived in Alma-Ata; she was her father’s mother. Step by step the grandmother moved over to them with all her belongings. Later, the elder sister moved to the Altai-Region, as well. At that time the Germans began to leave – for Germany among others. It gave Olga Ivanovna a lot of trouble to receive at least some money for her dwelling (local residents inhibited this), but finally she also left with her daughters for Germany – to a second-grade cousin. She still lives there, and she does not regret it.

For a long time Iraida Johannovna was in two minds about visiting her sister, but she finally made the trip recently.

The interview was held by Darya Svirina.

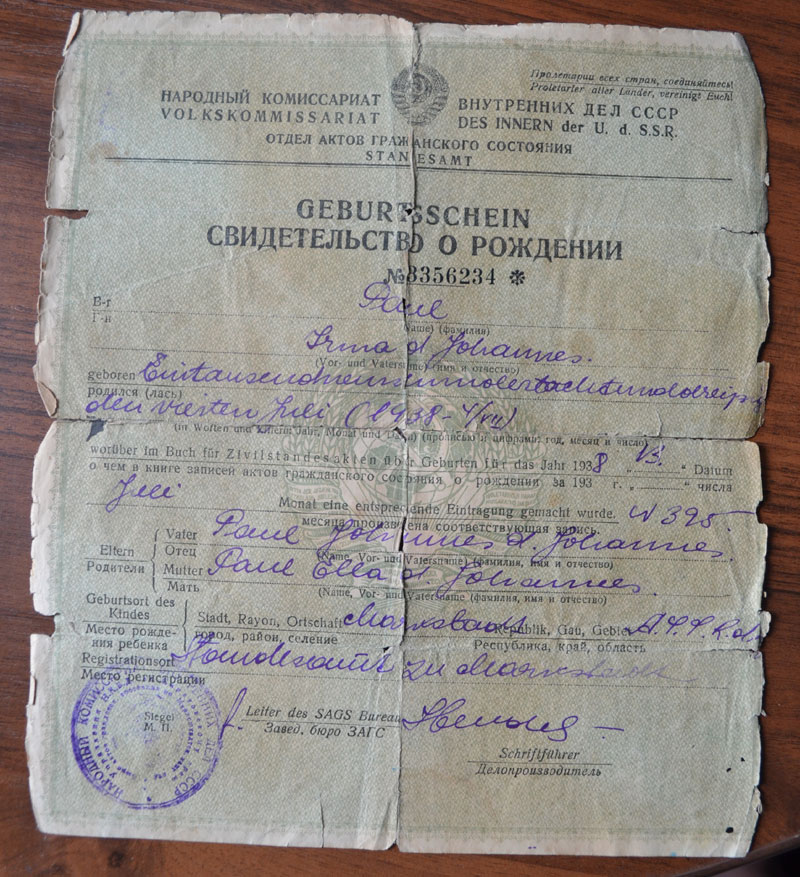

Iraida Johannovna (Ivanovna) Shustova‘s (Paul‘s) birth certificate

Iraida Johannovna’s father Johann Johannovich

Iraida Johannovna’s mother - Ella Johannovna. Photo from the time of her

professional training in Moscow

Family picture. Sitting – the mother, brother Vasiliy, the father; standing –

Iraida and her sister Olga

Rightmost Johann Johannovich, sitting; standing – Ella Johannovna. Next to

Ella Johannovna - Johann Johannovich‘s brother

Expedition of the V.P. Astafev State Pedagogic University Krasnoyarsk and the

Krasnoyarsk „Memorial“-Organization on the project „Anthropologic turn in

social-humanitarian sciences: Methodology of field research and practical

experience in the realization of narrative interviews“. (Sponsored by the

Mikhail-Prokhorov Foundation).