By A. Vologodsky and K. Zavoisky

Russian text: "Ìåðòâàÿ äîðîãà - ìóçåé êîììóíèçìà ïîä îòêðûòûì íåáîì"

èñòîðèè ÷åëîâå÷åñòâà êàæäàÿ âåëèêàÿ òèðàíèÿ îñòàâëÿëà â íàçèäàíèå ïîòîìêàì ñèìâîë ñâîåãî âåëè÷èÿ, êàêîé-íèáóäü ãèãàíòñêèé ïàìÿòíèê, ñðàáîòàííûé ðóêàìè åå ðàáîâ. Íî åñëè åãèïåòñêèå ïèðàìèäû äî ñèõ ïîð õðàíÿò îñòàíêè ôàðàîíîâ, ðèìñêèé àêâåäóê ñòîëåòèÿìè äîñòàâëÿë âîäó íàñåëåíèþ, òî ìîíóìåíòû-ñèìâîëû ýïîõè ñîöèàëèçìà ñòîëü æå áåñïëîäíû, êàê è ñàìà èäåÿ, èõ ïîðîäèâøàÿ. Ïî ñòàëèíñêèì êàíàëàì íå ïåðåâîçÿò ãðóçîâ, ãèäðîýëåêòðîñòàíöèè è ìîðÿ-âîäîõðàíèëèùà ðàçðóøèëè ïðèðîäó, òàê è íå îáåñïå÷èâ ñòðàíó ýëåêòðè÷åñòâîì, à óíûëûå ãîðîäñêèå äîìà-êîðîáêè ãîòîâû ðóõíóòü íà ãîëîâû èõ îáèòàòåëåé.

Äîðîãà Ñàëåõàðä-Èãàðêà, èëè 501-ÿ ñòðîéêà, êàê åå íàçûâàëè ìèëëèîíû ñîâåòñêèõ çýêîâ, íàâåðíîå, ñàìûé ÿðêèé òîìó ïðèìåð. Ýòà "äîðîãà â íèêóäà" ñêâîçü òàéãó è áîëîòà - íå åñòü ëè òà ñàìàÿ äîðîãà â "ñâåòëîå áóäóùåå", êîòîðóþ ñëàâèëè ñòàëèíñêèå àêûíû? Âñå, ÷òî îñòàëîñü îò íåå òåïåðü - ýòî óáîãèé çýêîâñêèé ñêàðá, èñêîðåæåííàÿ çåìëÿ äà ãîðû ðæàâåþùåãî èíñòðóìåíòàðèÿ. Äà åùå, áûòü ìîæåò, áðîäÿò â åå îêðåñòíîñòÿõ ïîòîìêè "âåðíûõ Ðóñëàíîâ", ó êîòîðûõ âèä êîëîííû íåâîëüíèêîâ óæå íå âûçûâàåò íèêàêèõ ðåôëåêñîâ.

Îñòàëèñü åùå ëåãåíäû. Äàæå â ìîå ëàãåðíîå âðåìÿ ñòàðûå çýêè âñïîìèíàëè 501-þ ñòðîéêó íåäîáðûì ñëîâîì. Áîëåå âñåãî îíè ñåòîâàëè íå íà ãîëîä è õîëîä, íå íà æåñòîêîñòü îáðàùåíèÿ - èõ-òî õâàòàëî âñþäó â ÃÓËÀÃå - íî èìåííî íà áåñöåëüíîñòü òâîðèìîãî òàì æåðòâîïðèíîøåíèÿ. Âåäü è ðàáó íå áåçðàçëè÷íî íà ÷òî ïîòðàòèëè åãî æèçíü.

Íå î òîì ëè è òåïåðü íàøè ìûñëè? Ãëÿäÿ íà ðàçâàëèíû áûëîé "âåëèêîé" ñòðîéêè êîììóíèçìà, íåâîëüíî äóìàåøü: çà÷åì âñå ýòî áûëî? Çà ÷òî? Èñêàòü îòâåò íà ýòîò âîïðîñ áóäóò, íàâåðíîå, ìíîãèå ïîêîëåíèÿ íàøèõ ïîòîìêîâ.

Âëàäèìèð Áóêîâñêèé

25 èþëÿ 92 ã.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Amidst the boundless marshes of the West-Siberian lowland, through the low polar forests and tundra, winding its way for hundreds of kilometers, stretches like a thin ribbon the deserted Salekhard-Igarka Railway Line. The loneliness of these parts and the almost complete absence of human cultural activity, contributed to the Dead Road and everything that was at one time connected with it, having been preserved almost intact. And today, forty years later, this gigantic museum of the Stalinist GULAG (the Chief Directorate of Concentration Camps) of the later years, stands under the open sky, bearing witness to the appalling conditions of the convicts' life, their slave labour, the chronic inefficiency of the communist system.

Among numerous other unsuccessful Stalinist "Great Constructions" (the White Sea Canal, The Baikal-Amur Main Railway Line and others) the epic of the Salekhard-Igarka Railway Line is distinguishable by its utter purposelessness. Initiated in a hurry by orders of the top Soviet leaders, the construction was absolutely unprepared in technological and organizational terms. The irresponsible Stalinist politicians and captains of industry were attracted to the project because it allowed them to use one of the so-called basic "advantages of socialism" -- the right of the ruling communist party to deprive the half-starved, war-devastated country of enormous means and resources by senselessly wasting them in an attempt to solve a problem that held promise of personal political success.

It is said that among the hired civilian builders of the construction there were to be found selfless enthusiasts inspired by the unprecedented scope and challenge of the task. It may have been so, though this kind of enthusiasm could hardly have been widespread. Rather, the majority of "enthusiasts" had no other way of sustaining their life in conditions of the Stalinist state-run economy with its mass deportations of population to Siberia for class or other reasons, its registration system of enslaving the workers, and the beggarly wages paid to them. It should be noted that all the volunteer 1participants of the project regarded it as quite natural that the work force of the "Construction of Communism" consisted of cruelly oppressed slaves -- prisoners of the Stalinist GULAG, on whose shoulders lay all the unbearable burden of the building work in natural conditions that were exceptionally harsh even by the standards of Northern Siberia. And those difficulties were multiplied by the blind inhuman voluntarism of the USSR top party politicians, the cowardice, incompetence and cruety of the industrial management.

The arduous toil of all that motley collective body was wasted: the construction has for ever remained uncompleted. Up to now not a single section has been used on the Dead Road which turned into a death road for dozens of thousands of prisoners. Today the final result of the gigantic Stalinist project seems quite logical. The decision the USSR government took on the construction of the Salekhard-Igarka Railway Line as well as the methods of its being translated into life repeated in miniature the monstrous experiment of the building of Socialism started by the Bolshevik Party in October 1917. The results turned out to be sufficiently similar.

In this book we propose to tell about the construction of the Dead Road and its builders. The contemporary original photo materials were obtained by the authors during their special expeditions to the Eastern sector of the Construction. They received historical and technicasl information about the Road mostly from oral sources: testimony of the participants of the construction. The old photos come from private and open state archives. Unfortunately the bulk of the GULAG archives concerning this Construction still remains closed for investigation, so our story will be incomplete. Still, we hope that the photo and documentary materials we have collected, will give the reader an adequate idea of the purposes and methods of the Stalinist-type economy and the scope and chcaracter of the economic activity of Soviet GULAG by the example of one of its most senseless creations -- the Salekhard-Igarka Railway Line.

The authors wish to express their heartfelt gratitude to all those who contributed to the publication of this photo-album: participant of the Dead Road Construction, former political prisoner L. Shereshevsky; the first independent investigators of the Salekhard-Igarka Railway Construction A. Nickolsky and A. Berzin who kindly placed at the authors' disposal part of the documents and photographs they had collected; participants of the expedition to the Dead Road headed by A. Vologodskii, co-author of the book, and particularly to M. Pokrovskaya, Y. Pototsky and D. Davidov who participated in processing the collected materials.

The authors' latest expeditions were sponsored by the Moscow "Memorial" Society.

When flying along the Polar Circle over the Northern part of the West-Siberian lowland, the traveller to-day will rarely see human habitations. For hundreds of kilometers there is not a single town, settlement or even hamlet. It is not by chance that these places are deserted here. The harsh natural conditions of Northern Siberia are too arduos for human life. In winter which lasts here eight months, the vast expanses are covered with snow up to two meters thick. The sun hardly ever appears from behind the horizon, the temperature drops to --50o C, with biting winds blowing. During the short polar summer people and animals are attacked by swarms of blood-sucking insects. All around there are marshes and marshes without end or bounds.

The aboriginal population -- Nenetses, Selcoups, Ketts had since old times engaged in fishing and hunting, leading a nomadic life. The deer, the foundation of polar life, provided man with food, warmth, and habitation, serving as a means of conveyance over the vast desert distances.

Photo by A. Vologodsky

Absence of roads, and the extremely low fertility of the land made other forms of existence practically impossible. Even the unpretentious and all-penetrating system of the Stalinist GULAG camps could extend its branches to this out-of-the-way place only towards the end of the 1940s. In those times the density of population here was as low as 1 person per 20 square kilometers. It is evident that building a long and expensive railway line in that God-forsaken part of Siberia was utterly unpromising. How then did it happen that a good one hundred thousand builders had, during four years, been stubbornly struggling to implement this insane plan?

In the post World-War 2 years the Soviet Communist system reached its efflorescence. Inspired by the victory over the Nazis, it was seeking to apply its unheard-of abilities. Preparing for future victories in its clashes with the West, the government of the half-starved war-devastated country paid primary attention to perfecting its military technology and strategy. In those years the USSR developed numerous military projects, in particular the project of super long-range missiles and that of the A-bomb which was unique for its complexity and cost. In all those undertakings the Communist leadership relied on the structure of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) it had established, headed at that time by the Stalinist hangman Lavrenty Beria, which concentrated in its hands huge research-project capacities, as well as the elaborately adjusted, unfailing mechanism of forced labour -- the GULAG. That gigantic consortium of slave camps had become by that time the USSR's biggest producer and contractor capable of concentrating, in a very short time, manpower sufficient, as it seemed to the country's leadership, to solve any economic tasks.

In expectation of successful completion of the work on the creation of super-powerful nuclear weapons, the Stalinist Politbureau (Political Bureau of the Soviet Communist Party) considered in advancee projects of their location. Under the influence of those considerations, the USSR Council of Ministers (CM) adopted, on February 4, 1947, decision No. 228-104ss on the necessity of constructing beyond the Ural Mountain Range, on the coast of the Arctic Ocean, a large secret military port with a great complex of structures, in particular a ship-repair plant, and a road to it. In April of the same year USSR CM adopted, without even requiring the designers present technological or economic substantiation of the the project, a decision to start construction of the road. Fulfillment of the project -- the prospecting and building work, was entrusted to the USSR MIA and the Glavsevmorput (Main Northern Sea Way) Administration.

The decision to create a huge strategic military base deep in the USSR territory might be partly explained by the inferiority complex of the then leadership of the country who still remembered how easily and quickly Hitler had reached Moscow, and what colossal efforts it had cost to develop a defense industry in the rear of the country. The leadership must have also been attracted by the prospect of inflicting blows, in case of an offensive war, from the deep rear on various points of the Northern Hemisphere by using the secret long-range missiles which were being devised at that time. All that has been said about the motives of the USSR leadership is, but our supposition. The true reasons for the construction of the port and the Road could probably be found among the Government documents, but even now, forty years later, they remain secret, inaccessible to investigators. Nevertheless, a more recent document is known, namely, the memorandum of P. K. Tatarintsev, Head of the Complex Northern Expedition of the Railway Project Administration (Zheldorproyekt), which explains the necessity of constructing the railway line and the seaport for quite peaceful reasons -- the needs of the region. The author of the memorandum says nothing about the purpose of building a huge port of the Northern Sea Route in a region whose waters are covered with a thick layer of ice about eight months of the year.

The version that the construction of the port and the Railway had a military background which was current among the builders erecting those giants, seems quite probable. The military purpose of the project is indirectly also confirmed by the priority and secrecy of the construction work, and, besides, by its practically unlimited financing. The USSR government took a decision to cover all the actual construction expenses by the actual outlays, in other words it cleared off all the expenditures incurred by the building administrations. The USSR government, economizing on all the needs of its citizens, was extremely generous when the matter concerned the main strategic military projects such as, for instance, the creation of nuclear weapons (sponsored, like the Dead Road Construction, by the USSR MIA).

However the case may be, the USSR government decided to build the future port in the lower reaches of the Ob inlet near Stone Cape. In March 1947, in accordance with the February USSR CM decision, 501 GULAG Administration which engaged in railway construction (called SULZHDS Northern Camps Railway Building Administration, and belonged to the so-called Main Administration of Railway Building Camps -- GULZHDS) energetically began to lay the 700 kilometer-long railway line from the Chum Station of the Kotlas-Vorkuta Railway to the North-East via Shchuchye and New Port towards Stone Cape. There was also a plan to build a 200 kilometer-long branch line as far as Labytnangy settlement on the left bank of the Ob.

The center of the railway line construction to Stone Cape was the settlement of Abez situated not far from the confluence of the river Usa and the Pechora where the Pechora GULZHDS Administration had been situated when it was laying the Kotlas-Vorkuta Road. The chief of the construction was chekist colonel V. A. Barabanov. In Abez was also situated the "headquarters column" -- a camp of prisoners working at the building administration, the GULAG building centers and cultural institutions, as well as production camp columns of motor-car repair service, bridge-builders, railwaymen, etc.

The building of the railway line began far to the North of Abez, in the direction of the Ob bank. The builders moved to the North at an average speed of 100 kilometers per season. By the spring of 1948, the rails of the road, fastened to the sleepers for the time being with two spikes only, had already reached the Polar Urals and had come up through the valley of the Ob river, close to the border of the Yamalo-Nenets National District.

At the opposite end of the line, the builders were moving from North to South. During the short polar summer, ships and lighters crawled down the Ob inlet to the future Novy Port (New Port) and Stone Cape, bringing people, coal, foodstuffs, timber, engines, engine fuel, tools and equipment for the future building. On the left high bank of the Ob inlet two-storey adobe houses were being built for the management and command, low barracks for the prisoners -- building materials were being unloaded all the time.

By the end of 1948, train service had been opened to "Obskaya" Station, and by a branch line to Labytnangy which provided passage to the river Ob.

But the builders of the Railway Line were not destined to reach Stone Cape. In 1948, the project-survey expedition discovered a fatal mistake in the Kremlin scheme. It was established that the Stone Cape region was not suitable for the location of a large seaport: the depth of this part of the Ob inlet didn't exceed 5 meters with only a meter and a and a half near its banks. After this belated "discovery" which was rather unpleasant for the Stalinist governing body, the builders had either to deepen the bottom of the Ob inlet up to 10 meters over a vast space, or to give up the building of the railway to Stone Cape. The former alternative was not even within Stalinism's power.

For this reason on January 29, 1949, the Council of Ministers resolved to put an end to the work, disregarding the money already spent on the construction of almost half the line (document No. 384-135ss). Completed was only a small part of the railway line between Chum and Labytnangy connecting the railway network of the European part of the country with the mouth of the Ob.

In spite of this monstrous economic error which had cost the country's national economy a pretty penny, the Politbureau didn't give up the idea of constructing a gigantic sea port in the Northern seas. By the same January resolution the projected port was transferred still farther East -- to the lower reaches of the Yenisei river. A new railway was ordered to be laid to the East, 1, 300 kilometers along the Polar circle across the West Siberian lowland, from the city of Salekhard on the right bank of the Ob, across the Labytnangy settlement to the settlement of Yermakovo on the left bank of the Yenisei, and then to the city of Igarka lying on its right bank.

The new variant of the railway was advertised as another triumph of Communist creative thought, as the first sector of the so-called Northern Trans-Siberian Main Line -- the cherished dream of the Stalinist regime. It was said that the railway would later be prolonged from Igarka to the North, up to the city of Dudinka and to the mining-and-steel works of the city of Norilsk, and then to the East up to Kolyma and the Okhotsk and Barents seas. (It thus turned out that the Railway Line was to unite the gigantic system of North-Siberian GULAG camps). Pathos of conquering the severe Siberian nature was propagated among the builders who were told that the Salekhard-Igarka Railway would promote the industrial development of the region, and by connecting the North-East of Siberia with the railway network of the European part of the country, it would help provide supplies to the port as well as to the Polar cities. The said connection was to be effected through the GULAG slave-constructed Kotlas-Vorkuta Railway Line which was transferred from MIA authority to the authority of the civilian Communications Ministry, which delivered to the central districts of the USSR coal from the mines of the northern cities of Vorkuta and Inta, oil fromthe Ukhta District and timber from the numerous GULESLAG (Administration of Timber Cutting Camps) situated on the territory of the Komi Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. It was rumored among the people that under each sleeper of that railway line a prisoner lay dead.

When adopting the decision on the immediate building of a railway in those Polar regions, the Soviet government had to foresee and take into account numerous unfavorable factors. To begin with, the construction was planned in a region remote from the industrial districts by thousands of kilometers. The natural resources of the region being very poor, it was imperative to bring to this Northern wilderness literally everything necessary both for the construction of the road and for the life of the people from timber which doesn't grow in the tundra to technical equipment and man-power. Transportation of all this had to be managed over an area which tremendously hampered its progress. In winter, motor vehicles could move sluggishly along reindeer paths only, and in summer, they would get bogged down in the marshy soil. This considerably increased the labour expenditure of the builders.

The task set by the Stalinist government not only complex and labour-consuming, was aggravated by the specific conditions of the Polar region. Abutments rammed into the permafrost are after some time forced out, icy lenses formed within the thick swampy ground, cause, when melting, downfalls of the earth and the settling of already built constructions. Builders carelessly disturbing the thin upper layer of the ground, change its heat insulation capacity. As a result, the permafrost border is displaced and the melted layers of the soil begin "to float" together with everything built on them.

Even if the builders had succeeded in completing the construction of the railway to start traffic on it, the above-mentioned processes would have, by slowly but hourly bending the rails, ruining the embankment, bridges and station buildings, reduced all their efforts to nought. The railway would have demanded continuous repairs throughout its whole length, and its exploitation would have proved unprecedentedly labour-intensive.

But let us imagine for a second that by some supreme effort it would have become possible to maintain the Salekhard -- Igarka railway in working condition. Then the problem would have arisen of economically inefficient cargo transportation, since the projected 1, 300 kilometer-long line was to run through impassable wasteland with only a few settlements of no great economic importance. Any sensible person would naturally wonder for what reason was it necessary to lay such a long line through the uninhabited and cheerless spaces of Polar Siberia, when more inhabited and more economically important parts of the USSR were in urgent need of means of communication.

It might have been expected that the organizers of the "Constructions of Communism" who had just routed the Ob Inlet project, would ask of themselves this question as well as many others. And without repeating their mistake they should have conducted a thorough technical investigation of the feasibility of a new construction to make all the necessary preparations. In this case the impossibility of building an efficient railroad and its hopelessness would have become obvious not after, but before billions of people's rubles were wasted and thousands of human lives were lost.

But nothing of the kind happened! The order issued by the leadership of the country again sternly demanded that the railroad be started in the shortest possible time. Nobody dared to contradict this order: the decree of the Council of Ministers to build the railroad was signed by the communist tyrant -- Comrade Joseph Stalin himself.

Òðóä â ÑÑÑÐ ÿâëÿåòñÿ äåëîì ÷åñòè, ñîâåñòè, äîáëåñòè è ãåðîéñòâà.

Photo by A. Vologodsky

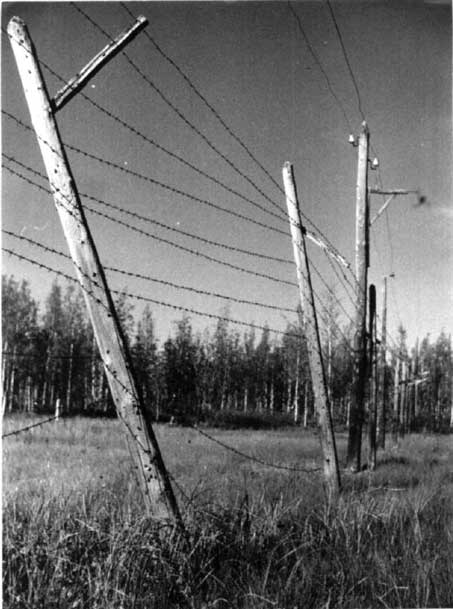

The center of the construction was temporarily located in the fish-factory district of Salekhard. The newcomer civilian workers lodged in private flats. The construction management occupied a school building. Not far away a plot of land was enclosed with barbed wire, marking the place for the “headquarters column” of prisoners working under the railway building Administration. The Salekhard wood-working plant switched over to serving the construction needs, turning into a slave enterprise complete with watch and guard. Rows of barbed wire were drawn up farther along the bank of the Poluy river, where the laying of rails to the Salekhard station was started, and where a special GULZHDS settlement was being hastily built. The slaves were brought to the columns by lorries under escort, and in absence of transport they were driven on foot surrounded by guardsmen. The Labytnangy settlement on the left bank of the Ob became the transit center via which the main slave manpower was being brought to the Dead Road. Building materials as well as equipment and machines necessary for life and construction were brought via Labytnangy which GULAG, as was mentioned above, had already connected by a branch line, with the Pechora Railroad. The quiet, patriarchal Siberian town of Salekhard was stunned by the sudden influx of builders, the lustre of golden shoulder-straps of high GULAG chiefs, the roar of unknown building machines, and the cheerless view of gray prisoners’ columns.

From here the builders moved East in the direction of Nadym. They had to begin preparatory work immediately after the issue of the Council of Ministers’ decree, in the middle of the Polar winter, without prospecting, with no design, nor estimate documentation. A winter road was laid out in the snow with the help of a tractor train, along which were hastily deployed production columns of prisoners—involuntary heroes of the new “Great Construction of Communism”. The prisoners themselves built, at sub-machine gun point, camps they were to live in. By summer the building of quarries, embankments, pipes, bridges had already begun on the first sections of the railroad.

In order to speed up the work former Building Administration 501 (SULZDS) which had just given up the construction of the half-built road to Stone Cape, was divided into two construction giants: Ob Administration 501 with its center in Salekhard, that was to lay the western part of the line 700 kilometers long, and Yenisei Administration 503 with its center first in Igarka and then in Yermakovo, which was to lay the 600 kilometer-long railway from the East to the West, to meet Administration 501. Communication between the builders and the administrations was maintained first by radio and later on by the pole telephone-telegraph line which had been drawn by the prisoners from Salekhard to Igarka along the future railroad. For inspection of the construction the authorities used the services of field and military aviation. Both construction Administrations were part of the GULZHDS system, which in its turn was under the USSR MIA jurisdiction.

According to the GULAG leadership plans the builders of both Administrations were to have met by 1952-53, on the bank of the river Pur, approximately in the middle of the 1, 300 km-long line. They understood on the top that efficiently to erect a huge construction on permafrost in a short time was an unrealizable task. For this reason the Administration was in a hurry first to lay the rails along the line without gaps, then to provide for the functioning of the railway at minimum capacity and thereafter, when trains would run, to complete the construction in real terms. In point of fact, even in its final state the Salekhard-Igarka Railway was to present a pitiable sight: the single-track with double-track sections, each 9 -- 14 kilometers long, was planned to launch at most 6 trains per twenty four hours.

The organization of the two Administrations’ work proceeding from the opposite direction was in addition characterized by almost complete absence of access roads in the region of the future railway. The builders moved forward in the following way: first, in winter time, they conveyed to the sections everything necessary for the construction during the coming season: slaves, building materials, equipment, foodstuffs. Then, along the already built highway, fresh forces were conveyed to be advanced further on for future use in the following building season. The leadership refused right away to build permanent highways along the railroad. In summer, wherever possible, rivers were used as access roads. As has already been said, the Communist government didn’t allow the contractors any time for prospecting work. Construction began simultaneously with the survey. Unforeseen circumstances caused at times the designers to lag behind the builders. Thus, for instance, on coming into the field, the designers of the USSR MIA Railway-Project, who had on more than one occasion devised GULAG railway construction schemes, discovered that the maps of the future Railway region were not detailed enough. So, the surveyors had first to draft new maps by means of air photography. It brought about an absurd situation: the delayed designers were often compelled to draw the railway line proceeding not from the local conditions, but from the location of the GULAG camps which had already been built by that time. The survey of the Dead Road as a whole, was finished only in 1952, just by the time this “Construction of Communism” had ceased to arouse enthusiasm among the high authorities, and was dying down.

The main part of the construction work on the road consisted in erecting the embankment for the future railway. In the exceptionally complex geological conditions of the region this kind of work proved to be too laborious, though the embankment was being built only in summer time, by simplified technology, and was formally approved by understated technical standards. Luckily enough, there was sand in abundance in the river valleys, wherein a considerable part of the line was laid. The sand was delivered to the embankment from the near sand-pits by dump trucks which were often stranded in the mud. Almost all timber was to be brought from other places and floated down the Ob, Taz and Yenisei rivers, in whose upper reaches it was stockpiled by the GULESLAG prisoners. Later on the railway itself began to help: small shunting locomotives with several goods trucks delivered the necessary building materials along the laid sections of the road.

It should be noted that at first the government lavishly supplied the construction. An unprecedented (by GULAG standards) amount of new heavy equipment was delivered from the center to the far-off spaces of Siberia. Even excavators were no rarity there. But the main instruments of earth-moving work remained the prisoners’ pick, shovel and wheelbarrow. The embankment was mostly raised in the old way: in single file, straining every nerve, the prisoners would push their heavily loaded wheelbarrows up a steep wooden ladder. On emptying the wheelbarrow each prisoner received a tag from the accounting clerk, and putting it into his pocket, would go down by another ladder. Other prisoners on the top of the embankment, levelled the sand with wooden rammers, while the guardsmen were dozing around the fires.

The delivery and laying of rails was carried out by special laying stations—trains of several trailers running along the built part of the railway. The workers-prisoners were kept in heated goods vans under guard. All the work of laying rails was done by hand. Wearing tarpaulin gauntlets the prisoners dragged the rails with long iron tongs up the embankment to put them upon the fixed sleepers. This work, like almost all the other kinds of work at the Dead Road construction, was laborious and inefficient.

In places where the railway was to cross streams that were shallow in summer, the builders erected wooden bridges across them or enclosed them in large-diameter concrete tubes placed under the rails. Hundreds of such crossings had to be built. The railway also crossed dozens of rivers including such high-water level rivers as the Taz, the Pur, the Nadym. The erection of bridges across such big rivers was a hard, and technically complex task requiring substantial additional materials and labour expenditures. For this reason at such crossings the builders at first usually erected temporary bridges on a detour, which later on, after the completion of the railway, were to be gradually replaced by permanent bridges. Envisaged were train-ferries across the river-giants the Ob and the Yenisei in summer, and a seasonal railway on the ice in winter (such an ice rail-crossing across the Ob was actually built and was functioning during the construction of the railway!).

In addition to the main work, the construction required the provision of numerous auxiliary economic and railway services. Along the road were being built engine depots, repair shops, plants, woodworking centers, iver moorages, dwelling houses and office buildings, and numerous other economic units. The building work overturned the life of the entire region, subordinating vast territories to the requirements of the railway project. The above mentioned settlement of Yermakovo where the Eastern Part Administration was situated, grew into a city with a population of 20 thousand, not counting the prisoners in the surrounding camps.

The first signs that the country’s supreme leadership began to lose interest in the railway appeared in 1951. The idea of a gigantic port being built in the Northern seas for some reason or other, forfeited for Stalin its former attractiveness. The Politbureau was gradually subscribing to the opinion that the government and its GULAG had again been too rash in taking the decision to build the Salekhard-Igarka Railway Line. Despite the fact that many talented engineers working at the construction adopted simple but most effective original designss of railway laying in conditions of permafrost, in most cases their ingenuity was to no purpose, for the built railway line was grossly imperfect.

The embankment raised in a hurry and by simplified technology was floating, washed out by spring waters, and blown off by winds, to sink into the swamps almost all along the railway. The bridges built on permafrost swelled and warped. As a result the newly built railway already required for its operation intensive efforts of numerous GULAG camps situated along the line. On the functioning parts of the railway the trains moved at a speed of 15 km/hour, often being derailed. In one of the deserted camps the authors’ expedition found, in 1989, a poster eloquently illustrating the situation: “Railwaymen! Put the tracks in good shape. Don’t let the trains get derailed! “Which other railway in the world has ever seen such a slogan!

Nevertheless the GULAG was determined to continue the building of the Railway Line until its final victory. In May 1952, a special commission was formed to consider the technical project worked out by the combined ZHELDORPROEKT Northern Expedition, and in October of the same year the project was sent to the State Building Committee, USSR CM, for official approval. This document proposed that the government allot another 3 billion roubles in addition to the three billion already spent, to put the Salekhard-Igarka Railway Line into working condition.

On March 25, 1953, soon after Stalin’s death, government deree No. 895-383ss, put a stop to the ruinous construction of the Chum-Salekhard-Igarka Railway Line. By that time Administration 501 had laid 400 km of railway, and Administration 503 -- 160 km from the city of Yermakovo in the direction of Salekhard, and some railway sections on the right bank of the Yenisei in the direction of Igarka. On two railway sections—Salekhard-Nadym (350 km) and Yermakovo-Yanov Stan (140 km) -- regular working traffic of trains was conducted. Besides, this Administration had built in Yermakovo a timber wharf, a saw-mill, a wood-working plant, a motor-repair works, an electric power station. A construction branch was established on the river Taz, which built a large settlement there, erected in most arduous conditions, an embankment, and laid a 10-15 km-long railway in the direction of Yermakovo. By the time the construction work was discontinued the two Administrations had expended over four billion rubles. From the moment the decision was taken to stop the construction, the railway began to die rapidly, turning into that which is now called “the Dead Road”. After an amnesty was declared for certain categories of convicts, the prisoner columns began to thin out. The propaganda enthusiasm waning, the towns and settlements became ever more deserted. With Stalinism weakened, the employed civilians moved to more lived-in regions. Everything that had for four years, been giving life to that vast region of Siberia, was overnight rendered necessary to nobody.

Ôîòî À.Âîëîãîäñêîãî

But the authorities still had many economic obligations in the region: it was necessary to do something about the immense number of buildings, transport units, implements and other equipment located on the vast spaces of the construction. At first they tried to conserve the construction and all its property, but later they came to regard such approach to the matter as too troublesome and unprofitable. Part of the most valuable equipment was taken back to the lived-in regions. In the 1960s, the Norilsk plant removed the rails from the right bank of the Yenisei.

It was seemingly decided to destroy the articles of daily use, to prevent the USSR citizens from getting them free of charge. In one of the railway camps the authors’ expeditions found an enormous cemetery of articles: heaps of boots cut to pieces with knives, piles of aluminium bowls, each with a hole acurately pierced with a bayonet just in the middle. It must have been an impressive sight to watch the USSR MIA guard soldiers destroying, by secret orders of the GULAG chiefs, the camp plates and dishes with their service weapons! It is also likely that what we took for bayonet traces might be the traces of common prisoner’s picks: the prisoners themselves might have been made to destroy the camp property. Whatever the case may be the destruction work required strenuous efforts. That’s why the bulk of the camp property was left to the mercy of fate. In 1957, four and a half years after the construction was stopped, a Lengiprotrans (a designers institution in Leningrad) expedition examined the western part of the railway from Salekhard to Nadym in order to determine its state. The expedition arrived at the conclusion that approximately one third of this part of the railway was utterly unfit for operation, the embankment required serious repairs, dozens of bridges wanted rebuilding as their bulging had reched an enormous immensity of about half a meter. Of all the erected constructions the only one still functioning was the pole-telephone-telegraph Salekhard-Igarka-Norilsk Line which had by that time been transferred from MIA control to the control of the USSR Ministry of Communications. The workers of the railway control points stationed at 30 km intervals, still maintained, using their own resources, the preserved parts of the railway in partly working condition, so that trolleys with light-weight trucks could run along the line, delivering, in summer, food and equipment to the railway.

In the early 1960s, enormously rich deposits of oil and gas were discovered in the vast area between the Ob and Yenisei rivers, which started the commertial development of the region. The uncompleted Dead Road which crossed this region, was, in December 1963, brought to the attention of the country’s new leadership, in the memorandum by P. K. Tatarintsev, author of the Chum-Salekhard-Igarka Railway Line, already mentioned above. His arguments in favour of the construction being resumed were much the same as in 1953. The new government bearing in mind Stalin’s failure, considered the project too risky and rejected the designer’s suggestion—new times had set in, and the GULAG was no longer the organization it had been before. The leadership designated a way out of the situation in the construction of gas pipe-lines from the deposit regions to the European part of the USSR. A single-track-railway was laid to Urengoy, to provide easier access to the region from the Surgut-Nizhnevartovsk Line. However, the problem of resuming work at the Dead Road had been debated in the USSR designers organizations until the mid-1970s.

At the end of the 1980s, expeditions of the authors of the present album examined the Eastern part of the Railway that had been completed by 1953. The photographs included in the album speak for themselves. In the most profound sense of the word, these terrible industrial landscapes of the still-born construction symbolize the natural finale of all the undertakings conceived by the Bolshevik system which had been staking on falsehood, violence and forced labour.

As has been mentioned above, work in all the sections of the Salekhard-Igarka Railway began with the setting up of so called “production columns”—complexes of buildings, each consisting of a prisoners camp, economic premises, barracks for the guards, and dwellings for the authorities. Those columns were placed at each 5 -- 7 km along the whole length of the railway section to be built during the coming year.

At intervals of 60 km, railway stations were built with side-tracks, ten to twelve columns on a stage of the line forming a unit. Men’s and women’s columns were placed separately, but men—and women-prisoners did the same work pouring gravel and sand, digging the frozen ground, loading and unloading transport waggons. Only those women were lucky who worked at the Central Sewing Plant where they were doing just women’s jobs—sewing quilted suits for the prisoners. The sections included not only building columns whose people were led out each morning with picks and shovels, crows and wheelbarrows to raise and level the embankment. There were columns to serve different purposes. For instance, transport columns were made up of railwaymen: engine-drivers and stokers, railway engineers and repairmen who serviced the railway. The road requiring continuous capital repairs, the camps kept on functioning even after parts of the line were put into operation. The principal burden of subduing nature fell to the parties of prisoners-pioneers. From habitable places they were sent forward, to areas where the rails ended. They were brought by sledges hooked to tractors, or by formations on foot, and from afar at times—by waterways, to remote places the designers appointed. There the prisoners were literally left to the mercy of fate, if not to count the constant GULAG guardianship. Those landing parties had, in the shortest possible time, in the most deplorable conditions, to render the place habitable and prepare a base for life and work for the arriving slave reinforcements. An eye-witness, engineer-surveyor A. Pobozhy draws in his notes an impressive picture of prisoners-pioneers unloading, in summer, enormous lighters and barges which had brought, by the Northern Sea Route to the bank of the Taz river, new slaves together with engines, railway cars, rails and sleepers. This GULAG landing party probably started the above-mentioned construction section of Building Administration 503 which laid the railway line from the Taz river in the direction of Yermakovo. Prisoners’ landing parties were not always brought to their destination in summer time. In the cold months their situation was more horrifying. They often couldn’t get wood to build shelters—there was only the tundra around. Until timber was delivered they had to live in most primitive conditions—in mud-huts or tents kept warm with “bricks” cut out of peat and moss turf. Polar cold and dampness penetrated into those dwellings nomatter how well the chinks were stuffed up with moss. Plank-beds were made of poles cut in the near tundra brushwood scientifically called “oppressed wood”. The prisoners slept on the plank-beds without mattresses, as was the rule in the GULAG. Their own wadded jackets and pea-jackets served them both as bedding and blankets. As the development of the area went on, building materials were delivered, and, the primitive temporary dwellings were replaced by capital wooden buildings more suitable for durable living, and in large centers—even by frame-barracks with plank-beds. In all the columns of the Dead Road the capital camps were built by one and the same scheme elaborated to the smallest detail, by the GULAG Administration as far back as the 1930s. Each camp was a square plot of land 200x200 meters, fenced off by 3 rows of barbed wire, which the GULAG authorities never ran out of. A high wire barrier with a peak was erected between two lower ones. In the corners of the square there were guard watch towers supplied with searchlights which at night poured blinding light into the zone, to prevent the prisoners who might conceive plans of escape, from hiding. For this important regime purpose in addition to building materials, barbed wire and instruments, movable power-stations were first thing delivered to each camp.

On the territory of the camp there were put up 5 or 6 prisoners barracks which were divided into two halves with separate entrances, each to house 40 people. In the middle of each half there was a stove made of bricks or of an old metal barrel. Along the walls were placed two storey plank-beds. On the territory of each camp there was a canteen, a bath-house for prisoners, sometimes a provision stall, a storehouse for personal belongings, a first-aid post, a library, a special section which dealt with the registration of prisoners and distribution of the work force, an operative-chekist department (OCHD), a so-called cultural and educational Department (CED) and others. Several houses, very much like camp barracks, were built near the camp, for the guards and dwellings for the authorities. It’s interesting to note that they sometimes allowed certain artistic liberty in the camp architecture of the Dead Road, subordinated as a whole to the purpose of crushing man’s individuality and keeping his psychological state at the level of beasts, which was typical of the Stalinist GULAG. In the half-ruined camp buildings, among the oppressively gloomy monotony, even now one can come across some decorative excesses pleasant to the eye: arches with ornamental decorations, summer-houses built by the prisoners themselves, and even still life pictures painted on the plastered barrack walls.

In each camp there was an indispensable penal solitary confinement isolator (PSCI) -- an inner camp prison, which was used for the suppression of those to whom camp life didn’t seem severe enough. PSCI situated near the watch-tower in one of the camp corners, was enclosed with an additional fence of barbed wire. It consisted of two unheated solitary cells, one common cell for 4 -- 6 people, and a warm room for the guard. The tiny cell windows had thick iron bars on them. The wooden doors with spy holes for watching the arrested were sheeted with iron. The prisoners were fed on cold food rationed according to the lowest standards.

Life of the railway camps in no way differed from that of the rest of the GULAG. L. Shereshevskiy, a former prisoner of the Dead Road, describes camp life in the following words: “Getting up early, bread ration, fish skilly, kasha (gruel) of God knows what grain—either boiled pearl-barley or millet blue because of the cauldrons’ poor tinning, boiled water without anything; roll-call of prisoners, taking them to the railway to work at a place fenced off by poles, with inscriptions on tablets “Restricted Area”, short smoke breaks by the fire, return to the zone in the evening under escort, and hard plank-beds. For entertainment there was the radio, sometimes newspapers, checkers and dominoes. The criminals drank very strong tea (so-called “chefir”) and played cards. After the evening roll-call, restless sleep in the cold barrack”.

When the construction was in full swing, the prisoners working at the Railway totalled 70 – 100 thousand people. Usually one camp contained 400 – 500 people. Larger camps were built in places where work was most intensive: at the construction of big bridges, plants, settlements, etc. The functional organization of those camps was approximately the same.

Although up till now the GULAG archives have remained secret, we know something of the people brought against their will to that gigantic Northern construction. Having no access to the archives, we are telling our story mainly on the basis of the oral evidence of a few survivors, former builders of the railway. Taking into account the scant information sources, the authors’ expedition to the Dead Road was lucky to find, in 1988, the card-index and summary account of prisoners’ movement of one of the camps in the Eastern part of the line.

Ïî ñèáèðñêîé äîðîãå ñòîëáû. Photo by A. Vologodsky

The documents contained data about 473 prisoners. The card-index included 305 personal cards, each showing the family name, Christian name and patronymic of the prisoner, the article of law by which he was convicted and his term of imprisonment. Some cards indicated the prisoner's nationality, education, profession and home address. The statistical conclusion made from studying and analyzing these card-index data confirmed and supplemented the oral evidence offered by the participants of the construction. Analysis of the card index data reveals that on the average half the number of prisoners were the so-called enemies of the people, i. e. persons sentenced to terms of imprisonment from 10 to 25 years, by shamefully notorious article No. 58 of the then criminal code punishing citizens for political crimes against the Stalinist regime. This article introduced several gradations of crimes from points 1-a and 3 (high treason in war time and collaboration with the enemy) to point 13 (belonging to the exploiter classes). It goes without saying that the majority of those «enemies of the people» had never committed any actions falling under this monstrous legislation. Some of them were involuntary victims of the Stalinist political campaigns and purges which shook the country. As for the others, the Communist state recruited them, , by using this unlawful method, as gratuitous work force to toil free of charge at its «great constructions».

The overwhelming majority of prisoners convicted by article No. 58 came from the USSR Western regions directly hit by World War 2. Very often the only guilt of those people was that before they got under the jurisdiction of the Communists, they had lived under other regimes which were not as ugly as they were depicted by Soviet propaganda. Among the Dead Road prisoners there were a great number of Soviet soldiers who had been taken prisoner by the Germans. Working in the Dead Road camps were German and Japanese POWs, so-called «historical counter-revolutionaries»—White-Guard emigrants the NKVD captured during the war in Europ, as well as members of underground organizations and guerrillas who had fought against the Nazis (they aroused particular suspicion and hostility on the part of Stalin and the prison authorities). Imprisoned there were also functionaries of different foreign parties and organizations, participants of the Polish Resistance who had fought against Hitler in the ranks of the Armia Krajowa, persons interned in Germany, and just Soviet citizens who had lived for some time on territories occupied by Hitler.

A special group of «enemies of the people» consisted of persons who had really participated in the armed struggle against the USSR for the independence of their territories—mostly inhabitants of Western Ukraine. Ukrainians constituted probably the largest national group of the Dead Road slaves.

Of special interest is the social structure of the Railway camps. Unlike 1937-38, among the prisoners convicted under article 58, there were almost no representatives of the anaemic party-state nomenclatura. To accomplish the grandiose Stalinist construction ideas sloggers were wanted. That's why the majority of «political» convicts serving their sentences on the Dead Road were workers and peasants, lorry-drivers, tractor-drivers, carpenters, joiners, electricians, etc. Another source that provided the camps with lots of well-trained workers was the decree issued June 4, 1947, «On the Struggle against Theft of Socialist Property». By this decree a USSR citizen could be sentenced (and was often sentenced!) to an excessively prolonged 25 years' camp imprisonment for a trifling misdemeanour, such as a few kilograms of grain taken home from a collective farm storehouse, or a reel of thread stolen from a factory. The number of convicts condemned by this decree made up 15 per cent of all prisoners.

Though the proportion of intellectuals in the Dead Road camps was not large, almost all intellectual professions were represented there. In the barracks could be found engineers, teachers, doctors, writers, painters, , composers, architects, lawyers, scientists, professional servicemen. For several years a real mobile theater functioned at the Railway, whose company consisted of professional actors condemned by article No. 58. Imprisoned in the camps were, for instance, the well-known theatre producer Leonid Obolensky, conductor N. Chernyatinsky, pianist V. Topilin, the famous atheletes brothers Starostin By far not all the intellectuals and professionals were given work to suit their specialities. Most of them served their term, doing, while they were strong enough, common work—with wheel barrow and shovel.

The remaining prisoners, a little less than 35 per cent, were persons convicted under criminal articles. That «swell mob» was a real disaster for the political prisoners whom they taunted, terrorized, robbed and even killed. The criminals, as a rule, unaccustomede to work, despised labour interests and labour relations. By fair means or foul they did their utmost to shirk work, appropriate the results of other people’s toil, and force out the political prisoners to harder working places. The criminal elite—the so-called «thieves by law»—did not participate in the common work. The camp authorities were rather indulgent to these phenomena, considering as they did, that the terror to which the criminals subjected the political prisoners, was an important measure to maintain camp and working discipline.

The GULAG Authorities of the Dead Road diversified the methods of terror with rewards for labour enthusiasm. If a prisoner fulfilled an especially urgent task he was renumerated with some additional foodstuffs, makhorka (inferior tobacco), or even alcohol. So-called «socialist emulation» was introduced among the prisoners. Teams of slaves assumed «socialist obligations»: the results were summed up by the Authorities who rewarded the half-starved, ragged winners, then and there, inside the barbed wire fence, with an additional food ration.

According to the propaganda assurances of the USSR Communist leadership, socialist emulation was, under Socialism, one of the main incentives to work. The effectiveness of this incentive seems rather doubtful. Both at liberty and behind barbed wires emulation amounted to upward distortion of results and juggling with facts. But the Communist Party stubbornly compelled the whole country to “compete” in the” socialist way. “ Likewise the camp authorities were obliged to “involve” in socialist emulation their wards who were deprived of every right. But the most surprising thing was that in their attempts to make the prisoners work efficiently, the GULAG work effectively the GULAG authorities who usually did their utmost to prevent the prisoners’ release ahead of time, and even used the least opportunity to prolong their term, reverted to the long—forgotten pre-war system of credit marks by which, provided a prisoner overfulfilled his day task while observing the regime rules, one day of his (or her) camp term was counted for two or even three days. This innovation really aroused the prisoners’ enthusiasm! Quite unprecedentedly, in 1947, throughout the GULAG camp network a voluntary recruitment of prisoners was announced to work at the Dead Road construction. Thousands of long-term prisoners from all parts of the country moved to the severe North in search of the desired forthcoming freedom. They were naturally transported there under escort through transit prisons, accompanied by shouts of the guards and the barking of watchogs. Because the GULAG regime envisaged for prisoners, even builders-volunteers, no other way of transportation. Simultaneously, driven to the Dead Road were fresh forces of Soviet citizens, naturally without their consent, who had just been sentenced by Stalinist courts to long terms of GULAG slavery. In early 1948, the chekist initiated volunteer game came to an end: the GULAG authorities issued an order to rid the camps of the central regions of the country of all political prisoners, and send them to build the Dead Road. As for the system of credit marks, they were alternately now cancelled, now introduced again.

The MIA guard officers and civilian builders enjoyed considerable privileges in comparison with the common Soviet citizens. To attract them to the construction, the Stalinist state offered them long holidays and furloughs, the highest Northern coefficient (that is, double payment), increasing it by 10 per cent each half year. Nevertheless they mostly led a dog’s life on the Dead Road. With or without their families they huddled for many years in dwellings essentially of the same type as the prisoners’ barracks, in an area ‘in which everyday amenities were out of the question. Though the Socialist state firmly kept its promises to this category of workers, their living standards could be considered high only in comparison with the monstrous poverty to which the Stalin regime doomed the overwhelming majority of its citizens.

It should be noted that most civilian builders didn’t get to the Dead Road of their own free will. They were recruited from among the so—called “special migrants”exiled to Siberia: class alien persons, persons of undesirable origin (for example, Germans), former convicts allowed to live at liberty, and other deportees who remained in those out-of-the-way places, realizing that return to their native parts with their documents would draw MIA attention and would end in a new arrest and a new camp term.

By far not all prisoners—Dead Road builders managed to survive even till such partial liberation. True, the situation at the Dead Road consruction was better than that at the other Stalinist constructions. Thus, A. Antonov-Ovseyenko, who was a camp prisoner of the neighbouring GULZHDS Kotlas-Vorkuta Railway line, testifies that in those Stalinist camps of the late 1930s—mid 1940s (like in the Hitlerite camps) the prisoner could endure the common work on the average not more than for three months running. Those of the greatest vitality got into the infirmary to return after some time to the column. The second failure at work, as a rule, ended in funeral, if one may so call the procedure of throwing the dead body into a pit without a coffin, but with a label with his record number tied to one of his legs, d—the camp passport kept by the authorities was following the prisoner in his wanderings around the GULAG). When there were two hundred corpses in the pit, the grave-diggers filled it with lumps of frozen soil.

According to Shereshevsky’s testimony, in the GULZHDS camps of the Salekhard-Igarka Railway line the mortality rate was lower. The “funeral”” procedure though of a like nature, was less depersonalized; the prisoners were sometimes buried even individually, and the label contained not only the record number of the dead, but also his family name, age, article of conviction and prison term. On his grave, whether on the camp cemetery or beside the road, a peg was put with a board on it. The board showed a conventional code of letters and figures, like a car number. A register of correspondence between numbers and family names of the dead was kept for accounts in the safe of the Special Personnel Department of the camp. These and other account data were passed on to the authorities by selective communication in a primitively ciphered form.

There are indications that in the late 1940s the deaththrate at the Dead Road was even lower than the average death-rate throughout the GULAG camps. The Railway camps were not severe-regimed, they did not aim at annihilating the prisoners. There were only several penalty columns there. The builders of the Dead Road received a meager ration, but they were not specially starved. However, in spite of the essential indulgence of the Dead Road camp regime by Stalinist standards, many thousands prisoner-builders never returned from those camps, perishing from diseases, exhaustive overwork, hard Polar life conditions, the tyranny of the criminals and the camp administration.

Driven to despair by the camp conditions, some individual prisoners ventured to escape which was a desperate step. In fact, such a decision bordered on insanity. Where could one escape if surrounding the camp were enormous spaces of the country turned by Stalin into a similar labor camp, packed with MVD informers, though not so strict a regime? Where was there to run; when for hundreds of kilometers around there were vast spaces of the Siberian North hostile to life. Only a narrow stripe of Railway stretched across the Tundra. Psychologically, with all his being man was holding on to this thread connecting him with life and giving him hope for a brighter future. The camp life conditions must certainly have been unbearably hard to make the prisoner venture to escape, dooming himself to certain death. No doubt, almost all the fugitives were caught. There were cases when they themselves returned, preferring severe punishment to starvation.

In terms of democracy and human rights, this kind of treatment of its subjects by the state looks like senseless mockery intended to harm them for no reason whatever. Still, analyzing the facts in the context of Soviet history, one begins to comprehend that at that last Stalinist “great construction” the Council of Ministers and the GULAG authorities, spared no equipment or investments, actually trying to effectively organize the builders’ work. Inspired by the forcible ideology of Bolshevism, they knew no better means to settle the tasks of the national economy than to drive the workers into squares of barbed wire, depriving them of will and rights, economizing on their wages, food and clothes. It might seem that the unlimited quantity of gratuitous labor, absence of manpower fluctuation, 9 hours’ working day (i. e. longer than at liberty), work without days off, absolute discipline and insignificant expenses to keep the workers under guard—all this was to demonstrate to the whole world the miracle of effectiveness of Communist production... But the miracle didn’t come to pass.

Stalin’s death in 1953, marked the end of this senseless undertaking. As has already been mentioned, the construction was stopped by the decree of the Council of Ministers. By the same decree the other GULAG “great constructions” were discontinued as “not meeting the national economy requirements”: the Main Turkmen Canal, the Samotechny Volga-Ural Canal, The Volga-Baltic Waterway, the hydroelectric power station on the lower Don, the Ust-Don Port, the Komsomolsk-Pobedino Railway over twenty hydro-technical and transport constructions altogether. That and some other decisions taken by the Council of Ministers reflected the serious changes in the structure of the Soviet state organization. Thus the Council of Ministers’ decree of March 18, 1953 envisaged the transference of most GULAG camps to the authority of the USSR Ministry of Justice. The MVD USSR Construction chief administrative boards (Glavks) were placed under the authority of the corresponding civil ministries. On March 27, the USSR Supreme Soviet issued a decree on amnesty, to release over a million GULAG prisoners. Simultaneously, the passport and regime limitations were abolished in 340 Soviet cities. All these measures cut the ground from under the feet of the Mighty Empire of the Stalinist camps. Meanwhile the GULAG problem remained open and required solution.

In 1956, N. Khrushtchev cautiously condemned Stalinism and half-opened the curtain hiding the scale of the camp system. The release began of political prisoners overlooked by by the amnesty. The Criminal Law was profoundly recast providing the citizens with better guarantees against the arbitrary rule of the courts. Nevertheless, finding himself behind barbed wire, the convict encountered camp conditions very similar to those of the former times.

After N. Khrustchev was stripped of his power in 1964, the idea of the GULAG underwent substantial changes. True, the communist system was not going to give up the use of forced labor, or the practice of keeping convicts in inhuman conditions. But at the new stage of socialism, in connection with cutting down the financing of the great constructions, and the fear of international reaction, a trivial idea was developed: instead of attempting to make the slave labour super-effective, it was decided to turn the camp system at least into a self-repaying organization. For a long time the creative efforts of KGB and MVD specialists were directed to elaborating this principle. In recent years they used modern computer techniques to achieve this cherished aim. The use of computers to raise the efficiency of slave labour at last brought about the desired results. The two and a half million-strong army of prisoners began to work on a self-repaying scheme for the good of their Socialist Motherland. Still, the slave-owning essence of the Soviet penitentiary system remained intact even after six years of Gorbachev’s Perestroika. Soviet socialism continued stubbornly to pursue the Dead Road policy, punishing people with labour. Those who didn’t wish to work in slavery for a beggarly remuneration were even threatened with a punishment cell and starvation rations.

The Soviet economy reports never mentioned the share of the output produced by slaves. Judging by many indications, it was not a small one. For instance, it is known that part of the contract on laying the Baikal-Amur Railway line undertaken in Brezhnev’s time, was given, as in former times, to GULAG. The only difference was that its slaves were presented by Soviet propaganda as Komsomol volunteers.

It is highly probable that in their everyday life Soviet people constantly come across articles made by contemporary slaves, because the GULAG produced a lot of household objects: furniture, glass ware, bricks, cement, a great variety of hardware and building materials. This slavery firm, had out of modesty, no special trade-mark for its goods.

To return to the Dead Road itself. Before finishing our narrative about its history, we would like to estimate the scope of damage inflicted on the USSR economy by the ignominious construction epopee of the Stalinist leadership. To make such an estimation is no easy task, but we’ll try at least to outline some ways of finding an answer to it.

As has already been stated, the expenditure estimates of the MVD USSR experts who designed the Salekhard-Igarka Railway line amounted to a sum of more than 6 billion roubles calculated at state prices of those times. That money was to be spent on the construction during a term of about 4 years. In order to realize how great a sum it was for the Soviet Union, it is enouh to state that it equalled 12. 5 per cent of all capital investments in the railway construction in the 1946-1950 five-year plan amounting to 2, 5 per cent of all the capital investments in the USSR during that period.

By 1953 the builders had been able to spend over a half of that money, which, as it turned out later, was simply thrown to the wind. This senseless expenditure is not to be looked upon as an expensive whim of a prosperous superpower. The money was withdrawn by the Stalinist leaders from the beggarly budget of the starving war ravaged country, and consequently irrevocably lost for the actually necessary programs of restoring the USSR national economy.

Full calculation of the damage, should besides, include another very important component part: had the money spent on the Railway, been cleverly invested in production or transportation development it could have given the state an income of several hundred per cent. This potential income which was not received should be added to the calculated damage. Thus, the calculation shows that the consequences of this one “Great Construction” alone was to affect the USSR economy for dozens of years, and the total losses caused by it most probably exceeded 10 billion roubles.

But even this figure doesn’t axhaust the damage inflicted on the country by the Stalinist construction adventure. The slaves of the GULAG, i. e. common Soviet citizens with all their working experience, with all their creative initiative, were lost for society for years, if not for ever. Had they lived a normal free life, they would have been of such benefit to the society as was utterly impossible when enslaved. How did the Stalinist designers of the “great constructions” take into account these considerations? Indeed, by what value could they estimate the incredible sufferings of the Dead Road builders, their senselessly exhaustive labour, their ruined health and lives, their wives’ widowhood, their children’s orphanhood? Without giving a thought to it, they equalled all these damages to naught.

All that has been said here equally applies to all the other Stalinist construction epics. Each “great construction” undertaken by the Communist leaders, caused the USSR national economy quite definite and very telling damage which fact was concealed from the country’s population and the rest of the world by the party propaganda media, by the efforts of the OGPU-MGB-KGB secret police, and also by the price disproportion deliberately maintained in the economy. Of these gigantic GULAG constructions, about twenty have remained unfinished. If you add up the huge sums of money wasted by the Communists and never returned to the people, you will understand why one of the richest countries of the world couldn’t get out of hunger and poverty.

A traveller finding himself today in the Dead Road region, of the Salekhard-Igarka Railway gets a surrealistic impression of the landscapes opening up before him. In the dense low forest which has grown along the Railway during the last 40 years, his glance is attracted by articles most unexpected for this uninhabited land, from table sewing machines to huge engines eaten by corrosion. Through the tree leaves he can see half-ruined camps encircled with barbed wire, dead settlements deserted by their dwellers, fantastic contours of the deserted town of Yermakovo. The embankment covered with bushes, with rotten crooked rails and ruined bridges stretches forward as far as the horizon. Moving down this Railway day after day, kilometer after kilometer you ever more clerly realize how great a destuctive force was contained in the senseless Bolshevik ideas—the ideas that intended to destroy the whole world to its foundation.

July-December 1991, Moscow

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. Memorandum on the examination of the Salekhard-Nadym Railway Line on location. A LENGIPROTRANS type-written report. Leningrad, 1957. (From the funds of the Central Railway Transport Museum, Leningrad).

2. Note on the building of the Chum-Salekhard-Igarka Railway Line. A LENGIPROTRANS type-written report. Leningrad, 1963. (From the funds of the Central Railway Transport Museum, Leningrad).

3. Pobozhy A. Dead Road. (From the notes of an engineer researcher). “Novy Mir” (“New World”), No. 8, 1964, Moscow.

4. Shereshevsky L. “500 Joyous”. “Krasny Sever” (The Red North), November 1988 -- January 1989, Salekhard.

5. Antonov-Ovseenko A. The Career of a Hangman. In: “Beriya: End of a Career”, Moscow, 1991.

6. Solzhenitsin A. GULAG Archipelago 1918-1956. YMKAPRESS, 1989, pp. 536; 542.

A. Vologodsky

K. Zavoisky

Èõ ïàðîâîç ñ ïóòè ñëåòåë... Photo by A. Vologodsky

© A. VOLOGODSKY and K. ZAVOISKY, 1991

Original text: HTTPS://cons3.narod.ru/DeadRoadENG001.html