Be damned, Kolyma,

that you bear the name of

such a wonderful planet.

You are forced to lose your

mind – and from here there’s

already no way going back.

The camp in Igil was built in 1947. The buildings from Novaya Zhiderba were transferred to this new place; some buildings were partly pulled down and the parts then transported away to Schaybino. G. Fedorov was appointed as head of the camp. A.A. Novikov, K.I. Kopylov and P. Snopchenko reported for duty here, and this was the place where the Shekhovtsovs, Lantsovs, Akuzins, Kibis’ and Dorokhovs lived. There were 120 convicts and more tha 100 – horses. There were 4 houses altogether, and in Staraya Zhiderba – 12. They called the guards in Igil „okhra“ (camp garrison; transl. note).

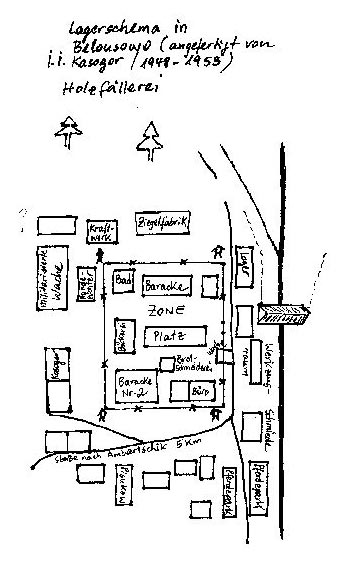

In the summer of 1947 they also organized a camp in Belousovo.

The place was chosen by watchman I.I. Kosogor and the technical manager Chuchko. The prisoners lived in tents first. They immediately started to fell trees and work for the different construction projects. To create an artificial inland sea the river Ambarchik was equipped with an impounding dam, 200 m in length, and a huge footgate. The dam still exists today and – looks quite passable, although the wooden floodgate became sooted by smoke in the course of time.

Remainders of the dam can also be found in Zhiderba nowadays. In the spring they used to dam up huge quantities of water. Then they would open the lockgates and start with the rafting of wood. In order to avoid the trunks to drift apart, they built further dams along the river-bed, which are also still in good condition. If you travel on the river Ambarchik today, you will be quite astonished, how much manpower, how much hard work has gone into these constructions, which served well for a period of about 5-8 years. After the area had been completely deforested, the camp sub-sectors moved to new places. In 1998 a group of students organized an expedition to Belousovo, where they found the remainders of a brickworks and fragments of tubs in which the bakers had kneaded all kinds of ingredients into a dough. They furthermore discovered the foundations of houses, two engines, floor coverings and several posts which then were part of the horse stables. Moreover they saw repaired cast iron kettles with a volumetric capacity of about 4-5 buckets; they had probably been used to cook meals over a camp fire. The students also detected a heap of rolls from Albert’s rack waggon, the cart-wheels of which still rotate on their axles when being pushed. According to the words of I.I. Kosogor there was a sawmill in this place, too. The clay needed for the brickworks was kneaded by the aid of horses, and on the clearings they used to make hay. Nowadays, most of the former hayfields are entirely brush-covered. The camp disposed of a prisoners’ commissary; it was managed by Ksenia Markovna Dubkova. There was a first-aid station, as well, both for convicts and civilians. Qualified physicians worked for the this aid station and the medical units. They lived on in the people’s memory till today. In some medical units they even used to perform operations.

The author of these lines was taken to the medical unit un Belousovo by his father to undergo treatment.

Along the river Berezovaya there were three barracks, a bakery and a shop. Exiles from the Ukraine worked there.

Thus, one may call the camp system of the taiga a nomadic system: having practically destroyed the resources of the surrounding woods, the camps were simply transferred to other places. The very first camps were situated in Ambarchik, Staraya Zhiderba, Kuzho ... the last one – in Stepanovka. Until now, more detailed or even chronometrical information about the different camps are not available. However, the GULag system began to exist in our region in 1938.

After the war, as from 1946, a special wood-rafting section was set up in Stepanovka; it was headed by Ivan Vasilevich Zhilinskiy. A little later it was led by foreman Danil Vasilevich Vinnik. He spent much time catching fish at one of the canals and tried to keep its mouth clean, so that it was easier for the fish to swim in; since that time the place is also called Vinnik canal. Documents witness that there were 11 families in Stepanovka in 1945 with a total population of 47 people.

The war brought about a new considerable increase in population: victims of political reprisals from the German Volga Republic were deporte to this place.

Below you will find the information of the UVD regional archives about how the distribution of the German families among the different villages of the Irbey district was organized, as noted down by V.K. Zberovskiy:

| Special Commandant’s Office of Irbey | Special Commandant’s Ofice of Tumakovo | ||||

| Villages | Families | Number of people | Villages | Families | Number of people |

|

Irbey Total |

35 140 |

169 608 |

Tumakovo Total |

50 151

|

207 655

|

A total of 291 families or 1263 individuals was scattered and settled all over the district. From the principle of how the people were settled, one may draw the following conclusions: the more villages there were, the higher was the number of German families sent there. Their distribution to the different commandant’s offices is more or less comprehensible: post and telecommunications, as well as communications (traffic facilities) probably were of considerable importance. However, there remains one question: why did Stepanovka and other camps along the river Tungir (Stariki, Galunka, etc.) belonged to the Tumakovsk commandant’s office? This obviously depended on the production needs: for here they were rafting wood. The rafted logs finally reached Khobanovo (not far from Kansk), and whenever the exiles had to get checked and registered with the commandant’s office, then Gumakovo was less far away than Irbey. They had to sign in and get registered once a month, as if they were still living at the Czar’s times. The personal files of the forcibly exiled people, the so-called victims of reprisals, comprised some very special pages showing the year, month and day, as well as the signature of the deportee. All files bore a seal with the inscription „secret“. Based on the ukase of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of the 13th of December 1955 and the order of the Ministry of the Interior No. 0601 of the 16th of December 1955, the legal position of the Germans and their family members who lived under special resettlement was improved, i.e. the legal restrictions imposed on them were abolished and declared null and avoid. As part of these measures their personal files of registration were transferred to the Krasnoyarsk regional archives of the administrative department of the Ministry of the Interior. And the special resettlers received a corresponding certificate.

The Germans were driven out of their places of residence in August 1941. The heads of the State were of the opinion that the Soviet Germans were henchmen of the fascists, and this what not yet all – they took measures to transfer them compulsorily in hot haste. But, for some reason or other, it seems that the German people did not produce more traitors than any other people in the USSR. They would have defended the USSR against the enemy – for it was their home country, after all, their mother earth, and they had already been living here for almost 200 years. Moreover, it was said, that they did not badly build their villages and organized their farm life very well. The people lost their houses, their own little subsidiary small-holding, their furniture and objects of value. They were merely allowed to take along two suitcases per person. However, they were handed out receipts, specifying the objects they had to leave behind. After 1994, on the basis of an order of the court and upon presentation of these receipts, some of them were granted a financial compensation for the sustained losses.

In the places of resettlement the local villagers avoided to look the Germans in the face; they treated them rudely, assuming that they were fascists. But when they realized that the Germans, too, were common people who, besides, were highly proficient in many things and fulfilled their tasks very diligently, they suddenly began to render them assistance.

The repressed Germans had to go through terrible humiliations. Poles, Letts, Lithuanians, Chetchens, Karachaevo-Cherkesses, Greeks and other ethnic groups were also deported, and there are indications of the fact that some people do not respect the Germans even nowadays. The reasons for such an attitude are – the war and the insufficient standard of education. Not without good reason many Germans left the country and went to settle in Germany. Supposedly 1 million of Germans departed from Russia – out of 2 millions.

The expellees had to gibe heart-wrenching signatures on a document that looked like this: surname, father’s name, first name, date of birth, resident of (name of the village, district, region), was made known the contents of the ukase of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of the 26.11.1948, whichs says that „I am going to be expelled for special resettlement to a different place – forever, without having the right to return to my previous place of residence and that, whenever trying to leave (to escape) from the assigned place of resettlement on my own authority, I will be sentenced to 20 years of forced labor“. Signatures of the expellee and a representative of the Ministry of the Interior. As far as one can remember, there have never been such strict and cruel measures in any other regime. How much did they hate the citizens of their own state to injure them to such an extent!

They drew up a questionnaire containing the personal data of each of the resettlers, who had to answer 21 questions altogether: surname, year of birth, nationality, citizenship, marital status, army service (yes/no), prisoner of war (yes/no), stays abroad (yes/no), previously convicted (yes/no), when expelled ... and others. Particularly shocking are the photos taken of the resettlers, photos, which remained well-preserved and are being kept in special envelopes. May these photographs, as well as all the other documents, which have been lying there for the past 50 years, lie there another 200 years! In those warm, light and dry places they are safe, after all! However, when your farther, with an entirely young face yet, looks at you from out of the picture or your grandfather, at the age of 40, then something will happen to you, for sure. The deep love for your fatherland develops a crack, your heart gets wounded again leaving a fresh, bitter scar, and you will always be deeply moved when hearing songs from Russia. Fortunately, those who stayed alive were granted a number of social allowances by the end of the century.

Moreover the personal files were kept in custody by observing particular criteria of registration: they were divided, for example, into Poles, Calmucks, Germans, dispossessed kulaks, etc. And all repressed persons were divided into four groups: deportees, internal exiles, special resettlers (forever), exiled settlers – so that they do not get confounded and can be found easily and quickly on demand. For these certificates are applied for by both expellees and their relatives. In 1995, for example, 112 000 individuals addressed themselves to the regional MVD archives to receive this document, and in 1998 – 9 000. How many, however, will not be able to ever contact the authorities and ask for these information anymore! All that speaks for the fact that hundreds of thousands of people were deported to our region. And the exiles themselves, who had to suffer a lot, left behind lots of remarkable things: settlements, roads, towns. They constituted their share to the development of the Krasnoyarsk region, which became their second home – and this is what they are still doing. Many of them will never leave this place, for they believe this spot drenched with their sweat to be the best in the world. And when they die, they will stay here, in the Sibirian earth, forever. Thus, many obeyed to the ukase: they were deported and stayed there for the rest of their life. In one of the old villages settled the families of A.I. Leongard (Leonhard), Keller, A. Gartman (Hartmann), G. (H.) Kremer (G. or H. Krämer), W.J. Schmidt, A. Weber and A.K. Schreiner and began to somehow organize their lives.

Elementary school, built in 1948

Towards the year 1950 Stepanovka numbered already 107 inhabitants – many

had come there, found a job and built themselves houses. In 1948 they opened the

elementary school (see photo). The building was erected by A.I. Leonhard’s

brigade. It is just behind the Vysotskiy’s house. The Pozdnoyev family lived

in it for many years. Liudmila Alekseevna Subbotina (Ivanova) was the second

teacher (on the photo with her husband Nikolay).

Towards the year 1950 Stepanovka numbered already 107 inhabitants – many

had come there, found a job and built themselves houses. In 1948 they opened the

elementary school (see photo). The building was erected by A.I. Leonhard’s

brigade. It is just behind the Vysotskiy’s house. The Pozdnoyev family lived

in it for many years. Liudmila Alekseevna Subbotina (Ivanova) was the second

teacher (on the photo with her husband Nikolay).

In 1951 a new school building was constructed opposite the Kopylovs (see

photo), which took two classes altogether. Today the building does not exist

anymore – it was pulled down.

In 1951 a new school building was constructed opposite the Kopylovs (see

photo), which took two classes altogether. Today the building does not exist

anymore – it was pulled down.

From Belousov Klyuch teacher Zinaida Ignatievna Ilinova (see photo) was transferred here. The lessons were held in two shifts: 1st and 3rd class, and 2nd and 4th. The school in Ambarchik existed till 1970. During the passed years Galina Yefimovna Maksimiva worked there as a teacher.

School built in 1951

Polina Ivanovna Kovryzhnykh and G.P. Vikentiev, a married couple, worked for the elementary school in Kasayevka. Till the opening of the school in Stepanovka the children went to school in the village of Stariki, were accomodated in apartments of the locals and went home for foodstuffs on free days. MOst of the firstgraders used self-made calculation sticks; they were made from the red halms of the silver willow. Everyday they brought their own inkpots to school in special bags. Their parents sewed an „Alphabet“ for them. Some children used to carry wooden cases, similar to big pencil-boxes, instead of satchels. They also had difficulties to provide the children with Young Pioneers’ neckerchieves – their mothers had to sew them themselves.

There was a telephone connection between Stariki, Romanovka and other settlements. It was even possible to make phonecalls to Kansk. In the 1960s the telephone was in the old village in M. Yemelyanenko’s apartment. Along the track section Stepanovka – Stariki you can still see a couple of telegraph poles from those times.

After the complete deforestation to the south of this area, as well as a general relaxation of the reprisals, the camps in these places were liquidated. The camp in Belousov Klyuch was transferred to Stepanovka. From there it was much easier to cultivate the taiga towards the west. They had already built quite a nice settlement there, and it was also not far to get to Irbey, Tugach and Kansk. In Belousovo prisoners used to work without the company of escorts till 1953.

And here are some information on the Tugachinsk separete forced labor camp sub-sector of the year 1949 regarding the rafting of wood. For example: on the river Kuzho – 33 days, on the Igil – 44 days, on the Ambarchik – 11 days, on the Kungus – 26 days, on the Tugach – 66 days. And about the separete forced labor camp sub-sector No. 7 (Kungusk camp sector): on the river Kungus – 67 days, on the AGul – 55 days, on the middle reaches of the river Kan – 52 days, and on its lower reaches, up to Lobanova – 85 days.

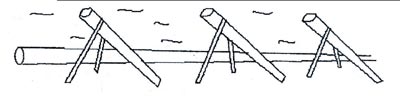

The log drivers spent the time between spring and autumn at the rafting base. Every now and then they would get released from there to help with the hay-harvest. And then came the Order No. 35 of February 1951 about the tranmission of the Stepanovsk rafting zone to the separate forced labor camp sub-sector No. 7, the forced labor camp sub-sector of Tugachinsk, the re-organization of the Stepanovsk camp sub-sector in the place, where the Stepanovsk rafting base was situated (with a capacity of 500 prisoners), and the construction of a garage destined for 6 cars. Moreover, they were to start with the building of a temporary trafficable road on the river Astashevka. When the ice-drift was over, the prisoners built special floating constructions to stop the timber floating on. This was done as shown below: a long whip was in a floating position. Upon the rise of the water the whip would also lift, thus making it impossible for the rafted timber to float apart to both sides of the riverbank. For that reason they additionally drove wooden stakes into the ground. They were given 5 – 8 days to finish the construction of these floating booms.

Information were found in the archives about the camp sector of Stepanovka and its temporary personnel in 1953:

|

Head |

Second Lieutenant |

Martynenko Ivan Grigorevich |

1400 Rbl |

|

Deputy of the head |

Lieutenant |

Medvetko Ivan Pavlovich |

----- |

|

Special unit |

Lieutenant |

Vozovik Petr Grigorevich |

700 Rbl |

|

Culture and Education Department |

First Lieutenant |

Shvedenko Grigoriy Afanasevich |

700 Rbl |

|

Medical unit |

Physician |

Zubarev Aleksey Nikiforovich |

690 Rbl |

The procurement plan for the year 1953 showed up to 400 cubic meters. And this is a list about which scope of duties the people were working for:

The task was to transfer the old buildings, the head-quarters, the bakery and the barracks from the camp sector of Belousov Klyuch to Stepanovka.

The camp zone, shaped like a square, was organized on the territory of the guardroom, besides the (former) shop, in the old village (behind Molodezhnaya street), up to the garage that belonged to the timber section. It was surrounded by a barbed wire fence with watch towers at the four corners. There were guard dogs, too. Within the zone there were four barracks for the prisoners, a canteen, which was housed in the same building as the club, a bath-house, an office and an isolator. The big gates pointed in the direction of the river Kungus. The camp was extended by a garage equipped with a huge sawing device. They used to bring the timber from the wood section by horses – via the wooden railroad line. One waggon had a capacity of 6 – 8 cubic meters of timber. When the prisoners arrived from Norilsk, the number of „blatnye“ (criminals; translator’s note) increased considerably. Later, however, otdinary prisoners gained the upper hand, and the criminals were sent away to other camps. A little further to the north they erected a nice building for the guards. This was called „vsvod“ in common parlance. The building was mainly constructed of larch and pine beams of a size of 20 x 20 cm. The outside walls were roughcasted; inside, however, the walls were decorated with beautiful mural paintings. There was an exercise room with sports equipment: a horizontal bar, a climbing pool, a climbing frame, ropes and a balance beam. The dog handlers trained their dogs. Once, a young bear was kept in the yard on a chain. There was a dancing ground, as well as a cinema for use in the summer. There the young people of Stepanovka would spend their time to relax. The camp leaders were:

1951-1952: first lieutenant Polyakov, 1952-1953: first lieutenant Losew, apart from that, until 1957: G. Martynenko, captain D.Y. Subbotin, captain Strunin, Shavlyak.

K.G. Shablovinskiy and Yegorov were the heads of the rafting section. The number of prisoners ran up to 600 (see map of the camp).

Map of the Stepanovsk camp

It is a remarkable fact that the whole camp zone area, as well as the „vsvod“ were maintained in an ideal way. They set great store of cleanliness and tidiness – in the summer there were even flowerbeds with beautiful flower. The people who had been deprived of freedom tried their best to improve things, to make things look more beautiful to get settled in their whereabouts to some extent. Those living in freedom were not that pedantic for some reason or other. It sometimes happened that prisoners tried to escape. As a consequence, the nerves of the village people were strained to breaking point for days – until the fugative had finally been found. Soldiers with dogs combed every nook and crammy. From time to time fugatives were even killed.

The prisoners worked for the lumbering section along the rivers Parfenovka and Samsonovka. Every day they were taken to the woodland under escort, and there were watch-towers everywhere on the frozen ground. In the summer, when returning to the camp after work, the prisoners often presented the children with skilfully bound wreathes of flowers or brought along eagle owls and other gifts from the forest.

The camp was keeping a great number of horses at that time. The hay needed to feed them was mowed both by prisoners and villagers. After the shutdown of the camp the horse park was maintained until the middle of the 1970s. In earlier times they had used horses to transport hay and firewood. The people knew almost all horses by their names. The representatives of the camp authorities always went in beautiful Cossack carriages to get from one camp sub-sector to another, whereby the used quick horses only. The quickest horse was Khmara, the best work horse – Galka. The Kazakh Dadyrov worked there as a groom. The camp disposed of 118 horses altogether.

The prisoners often gave concerts in the fire station or the club. They sang songs, recited poems and performed various kinds of tricks. The people would look on them with interest.

On the territory, where the camp garage was situated, a little brickworks was in operation. They provided the whole village with bricks. The stones were of an extraordinarily good quality; in some houses they still nowadays prove to be a reliable material. The office of the management was full of placards with slogans such as: „The cader units drop every decision“. There were lots of posters, graphs, notice boards, etc.

On the 5th of March 1953, the day of Y.V. Stalin’s death, the whole village was mourning. The houses were draped with black flags, the warning sirens were whining. It is to be supposed that the prisoners in many camps felt a sort of relief, since they now had great hopes of a turn for the better.

We have already noticed the negative consequences of camp life, and we will have to add that today, as well, people committed every kind of crimes. The most alarming of all, however, is the number of murders, which, in most cases, happen under the influence of alcohol. A whole settlement will suffer a lot, when a father killed his son, a husband his wife or the other way round.

In spite of all the negative moments, the local residents received quite a good medical care, for the pysicians in the camp zones had a good practical knowledge, and they also treated the local inhabitants. Even today people on our region have pleasant memories of a surgeon called Narodniy. The presentation of movies, the performance of theater plays, common dances – all this introduced my country people to culture. Moreover, the camp sawmill and the bricksworks provided the people with all necessary materials, and the civilian population was even allowed to use the bath-houses. Of course, the military uniform of the guards left traces in the minds of the future officers. After the released prisoners had left into freedom, they married local residents and stayed in the place for the rest of their life. After the disspolution of the camp the barracks served as lodgings, the club became part of the settlement, the garage became linked up with the forest district. The former guardroom first served as a school, later it was made into a bath-house. Maybe the reader will not be seized by emotion when hearing about such changes, but I think it is worthwhile to accept them as facts.

The camp existed till 1957. Then it was dissolved. Some of those who had served their sentence by that time, stayed there to work. Some of the guards did not want to leave the place, either: N.A. Pashkovskiy, M.T. Smolyarov, V.I. Ilinov, P. Govorukha, V.I. Sharypov, Pisunov and others.

On the whole, the existence of the camp left deep traces in the history of the settlement, and the consequences can be recognized until today (camp slang, striking criminality, use of swearwords, etc.). The camps in our woodlands were organized as from the year 1938; they existed till 1957. The GULag system was prevailing here for about two decades, the GULag, which one might call a state within the state. Of course, it left its traces in everyday life, manners and customs of our country people. We somehow managed to get of the GULag, many a person came into internal exil, were deprived of freedom, others worked as guards and served as camp personnel, which means that we are all from the camp. 40 years have passed since then. Two generations have grown up without being confronted with camp life; let us hope that they will be less influenced by the camp spirit, that they will feel free and more democratic.

Let us stress out once again that this system was no punishment system, but rather an executive system, for people used to serve their sentence here by judgement. Many people spent their whole youth in this place, many got married and stayed for the rest of their life. The Siberian earth became their new home. Unfortunately, dozens of indiciduals have already passed away, and we still do not know, where they are buried. We will, however, continue our search.

Victor Yakovlevich Oberman

„About my country people and – a little about myself“

Krasnoyarsk, 2000