Born in 1941.

Born in 1941.

In her early years Ella Gottliebovna lived in the hamlet of Furmanovo, Engels District, Saratov Region. This are was exclusively populated by Germans; you would not hear anybody talk on another language but German.

Her mother was called Frieda Petrovna Schefer (Schäfer). Before the resettlement she worked for a sovkhoz, were she grew different kinds of vegetables on a melon plantation. Her father was named Gottlieb Nikolaevich Schefer (Schäfer); he was working for s sovkhoz, too. When the brother was four years old, he was befallen by a terminal illness. The mother went to visit him in the hospital and – contracted the same disease. Both died in 1944, when Ella Gottliebovna was just two years old. Frieda Petrovna died at the age of 30. The father was killed in the labour army – this happened in 1944, as well.

The family was deported in 1941, when Ella Gottliebovna was two months old. She cannot remember their removal, but she learned several things from what her grandmother told her. They were not allowed to take along more than 25 kg of luggage; they were given 24 hours to pack everything up. Among others, the decided to take along a soinning wheel, which they have been keeping up to this day. They were transported on freightcars; the trip lasted several months. Finally they reached the Pirovsk District, the village of Troitsa, where they were accomodated with the Uskovykh family. In this little hamlet one of the streets was populated by Germans only. According to what Ella Gottliebovna recalls, this street looked very clean and was abundantly covered with vegetation. After their removal they did not receive any compensation for all the property they had been forced to leave behind in their former places of residence. There were documents, isuued in her father’s name, regarding some obligation to return the confiscated property, but grandmother did not expect anything from them and decided to throw them away.

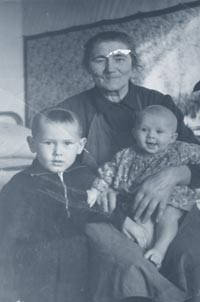

Her grandmother on the mother’s side replaced her deceased mother. E.G. remembers how she lived together with her grandmother and aunt. The women worked in the fields, where the often stayed for several weeks without coming home. During this time E.G. would spend the time cooking meals and fulfilling various tasks and duties in the household. The old people living in Troitsa met the Germans with disrespect. But the newcomers were never insulted by their contemporaries. In this village everybody was subject to paying taxes, in the form of eggs and butter. One of the women who lived in this village was unable to pay the taxes imposed on her, because she was not good enough in farming. They put her to prison several times.

E.G’s grandmother used to wear black clothes only, mourning garments, and she did this for several reasons. First of all, and this was the main reason, she had lost many relatives, among them two husbands. Apart from this often reminisced about the solid, two-storeyed house and the big farm which she had been forced to leave behind in Furmanova. There they had had a big garden and even cows.

In 1951 the Soviet government passed an ukase allowing all Germans to return to their home towns or villages (AB – this is an obvious error. In 1956 they were released from the state of being special resettlers, but they were not permitted to go back to their previous places of residence). Many people left the place.

In E.G’s case it came to nothing, for their were nothing but women within the family at that time, and so they all stayed where they were.

Having finished four years of basic education, E.G. went to a residential school in Velikovo, where they gave lessons to both Russian and German children. Just like in Furmanovo, their contemporaries did not utter any vicious or rude remarks towards the Germans, nobody called E.G. a “German” or a “Fascist”. There was a shop in the village, where the schoolchildren could by schoolbooks, exercise books and blotting paper.

During her childhood E.G. had a friend called Zina; she was a merchant’s daughter – a girl of 11 years at that time. Her family treated E.G. as she were their own daughter. They would fondle her head, carry her to the bathroom on their arms, wash and feed her.

In her schooldays E.G. was a rather vivid and quick-witted girl, who always enjoyed skylarking. Just to give an example: she and some other girls fixed little bells to the windows of the houses, and whenever there was a fresh beeze, the bells would attract the attention of the people around.

While she attended the boarding school, she became a pioneer and later a member of the Young Communists’ League. Her grandmother disapproved her joining the komsomol organization, for she first and foremost associated this with Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, who had given away her life for her fatherland’s sake. Grandmother was afraid that her only granddaughter, being a an orphan, might do the same thing. Being well aware of her grandmother’s attitude, E.G. became a member of the komsomol on the sly.

In 1953 Stalin passed away. When the news became public, all classes were

cancelled at school, teachers and students were moved to tears during the

mourning ceremony. Of all people E.G. knew personally, her mgrandmother was the

only one who did not break into tears. She just turned round an went away, when

she heard the news from Emma. E.G. supposes that, even after Stalin had died,

her grandmother still feared to talk about certain issues within the family. All

were crying “on the sly”.

In 1953 Stalin passed away. When the news became public, all classes were

cancelled at school, teachers and students were moved to tears during the

mourning ceremony. Of all people E.G. knew personally, her mgrandmother was the

only one who did not break into tears. She just turned round an went away, when

she heard the news from Emma. E.G. supposes that, even after Stalin had died,

her grandmother still feared to talk about certain issues within the family. All

were crying “on the sly”.

At that time dresses with “lampion” sleeves and wedge-shaped skirts came into vogue.

At the age of fourteen she left the boarding school and went to work for a kolkhoz farm as a herdswoman. The workers were mainly Germans; Russians did not like to work. The were paid a salary, but E.G. did not receive the earned money herself. It was handed over to her grandmother. They had to work for thekolkhoz farm from 4 o’clock in themorning till 9 o’clock in the evening. They went to the neighbouring village for lunch, for it was not so far away. It was comparatively common to decorate shock workers.

Having worked there for a period of five years, E.G. suddenly disappeared to the Yenisey District to work for the timber industry, where she shovelled snow. The labourers did not receive any warm clothes; they had to buy all garments themselves from their hard-earned money. She did not stay there for long.

Afterwards she went to Abakan to train as a baker . Later she found a job for a bakery in Vorsk. She has been working as the head of the shop for more than twenty years

In the course of time the village decayed, there were no schools to teach the children, and so they were forced to remove to Novokargino.

One of the most vivid memories from her childhood is the vizualization of her

neighbour’s fate. Shura was head over heals in love with a German named Vitya,

who returned her affection. But Vitya’s mother was against their marriage. Both

mothers set out for the neighbouring village and found her another bridegroom.

During the wedding ceremony Shura asked to send for Vitya, in order to say

godd-bye to him. Vitya packed his bags and insulted his mother in high words;

after having told her that she would never see him again, he disappeared … for

more than fifteen years. During this time he got married and finally returned.

Shura, sooner or later, came to terms with the situation, the more since she had

a very good husband and cuddy children.

One of the most vivid memories from her childhood is the vizualization of her

neighbour’s fate. Shura was head over heals in love with a German named Vitya,

who returned her affection. But Vitya’s mother was against their marriage. Both

mothers set out for the neighbouring village and found her another bridegroom.

During the wedding ceremony Shura asked to send for Vitya, in order to say

godd-bye to him. Vitya packed his bags and insulted his mother in high words;

after having told her that she would never see him again, he disappeared … for

more than fifteen years. During this time he got married and finally returned.

Shura, sooner or later, came to terms with the situation, the more since she had

a very good husband and cuddy children.

The second thing she recalls is a portrait of her mother. In fact, E.G. only learned that her grandmother was not her mother when she was nine years old. Nevertheless, she called her “Mum” till the very end. She recalls that she always began to cry when she was standing in front of her mother’s portrait, often without even knowing why. She thinks it is true when people say that orphans are always well-protected by some apparition around; she always had the feeling that somone was near to look after her.

She also remembers that once a man intended to visit his previous place of

residence to check up what had happened to their abandoned houses. He left the

place without having asked the authorities for permission; by a fraction of an

inch they had sent him to prison for this deliquency. Having arrived in his

former home village he noticed that all houses, including his own, which had

been occupied by Germans before the deportation were now inhabited by Russians.

When the Russians saw the man they left their houses and thwarted him with

shotguns in their hands.

She also remembers that once a man intended to visit his previous place of

residence to check up what had happened to their abandoned houses. He left the

place without having asked the authorities for permission; by a fraction of an

inch they had sent him to prison for this deliquency. Having arrived in his

former home village he noticed that all houses, including his own, which had

been occupied by Germans before the deportation were now inhabited by Russians.

When the Russians saw the man they left their houses and thwarted him with

shotguns in their hands.

We are also familiar with our aunt’s fate. After her complete family had been displaced to the Pirovsk District, she met her future husband Fedor. His family lived in Moscow; he was a Moscovitan himself. Later, after Fedor, together with Vlassov, had been deported to the Pirovsk District, his family broke away from him.

E.G’s grandmother died at the age of ninty. She very well recalled her German mother tongue even when she was advanced in years. E.G. is not really sure but nevertheless suspects that she bore Stalin a grudge, because he was the one who lured everybody on to destruction, Russians as well as Germans, and caused them such a hard lot.

Interviewed by Maria Pichueva and Irina Saranova

(AB – comments by Aleksei Babiy, Krasnoyarsk “Memorial”)

Fifth expedition of history and human rights, Novokargino 2008